The Griot of the Lens

In the heart of Bamako, where history whispers through the streets and culture pulses in the air, a young girl once wandered, absorbing the world around her. She was Fatoumata Diabaté, a name that would soon be synonymous with storytelling through photography. From those bustling Malian streets to international acclaim, her journey is a testament to vision, resilience, and the power of an image.

A Childhood Framed by Legacy

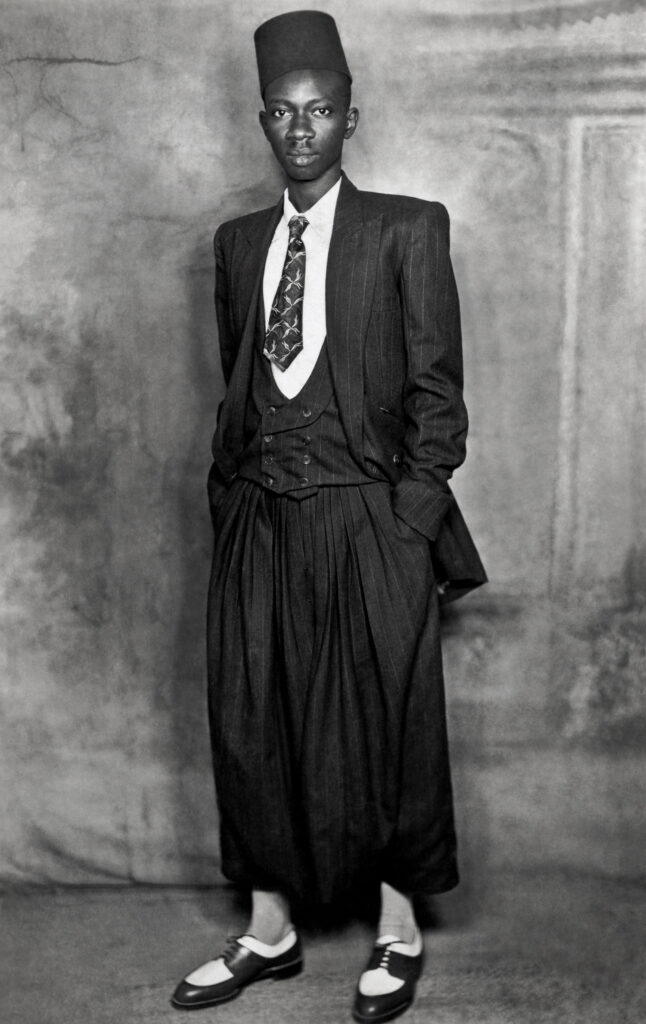

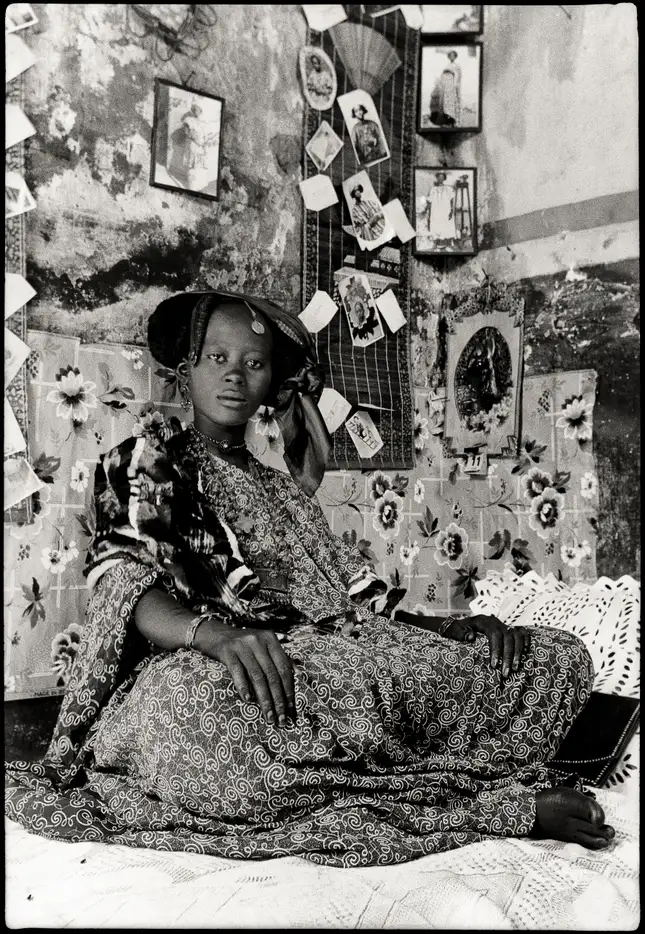

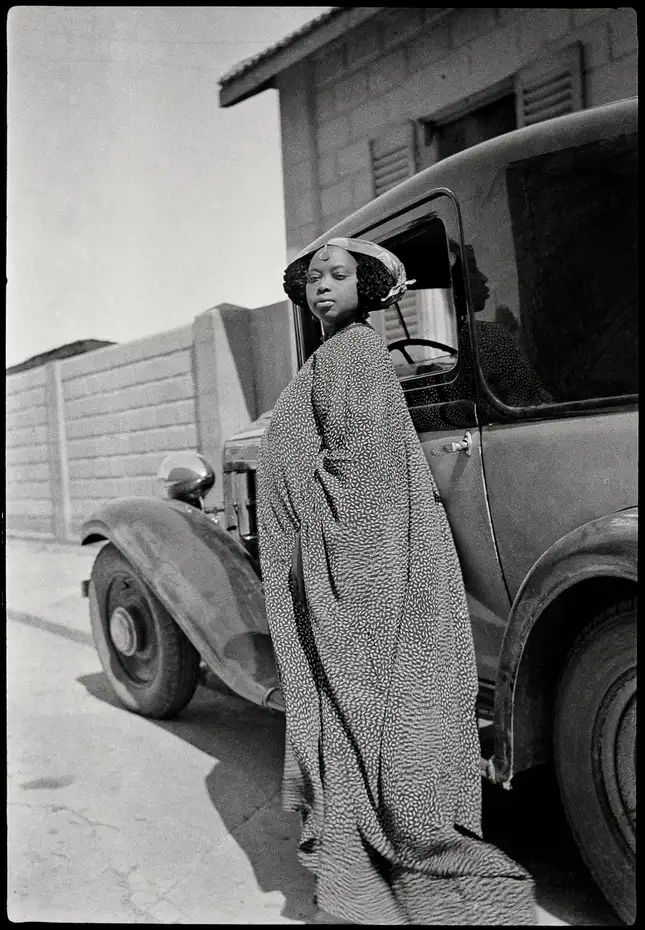

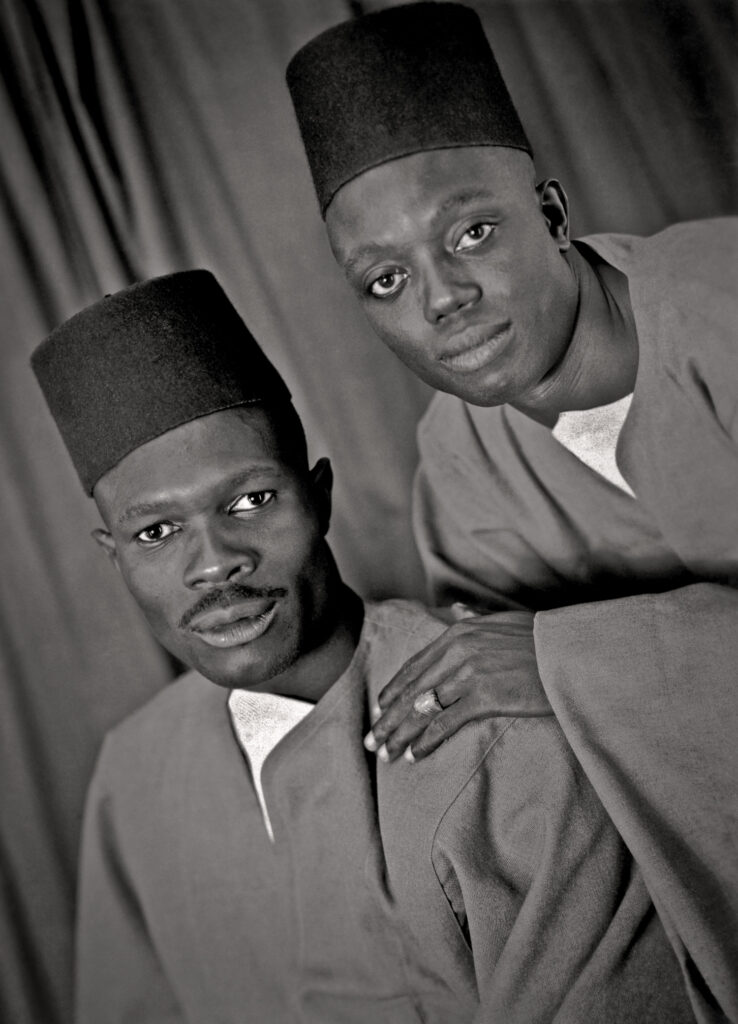

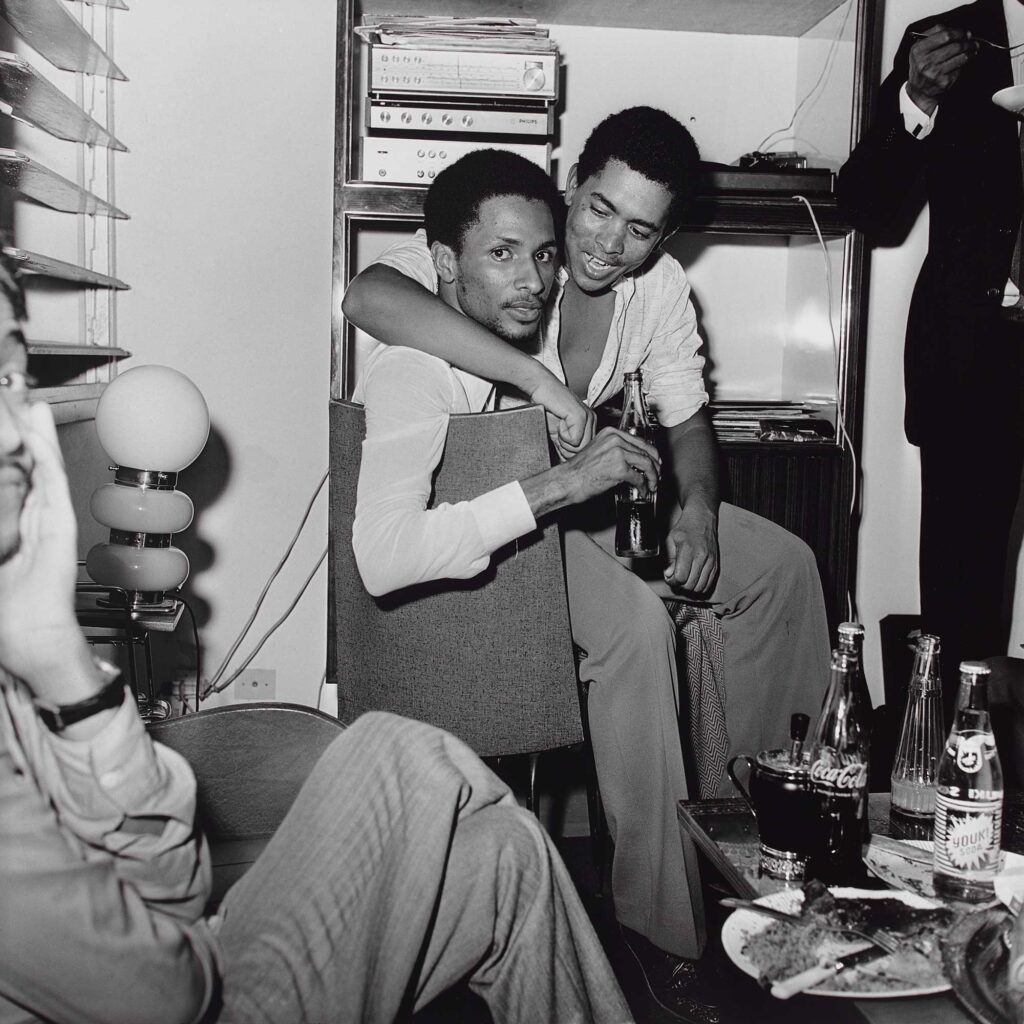

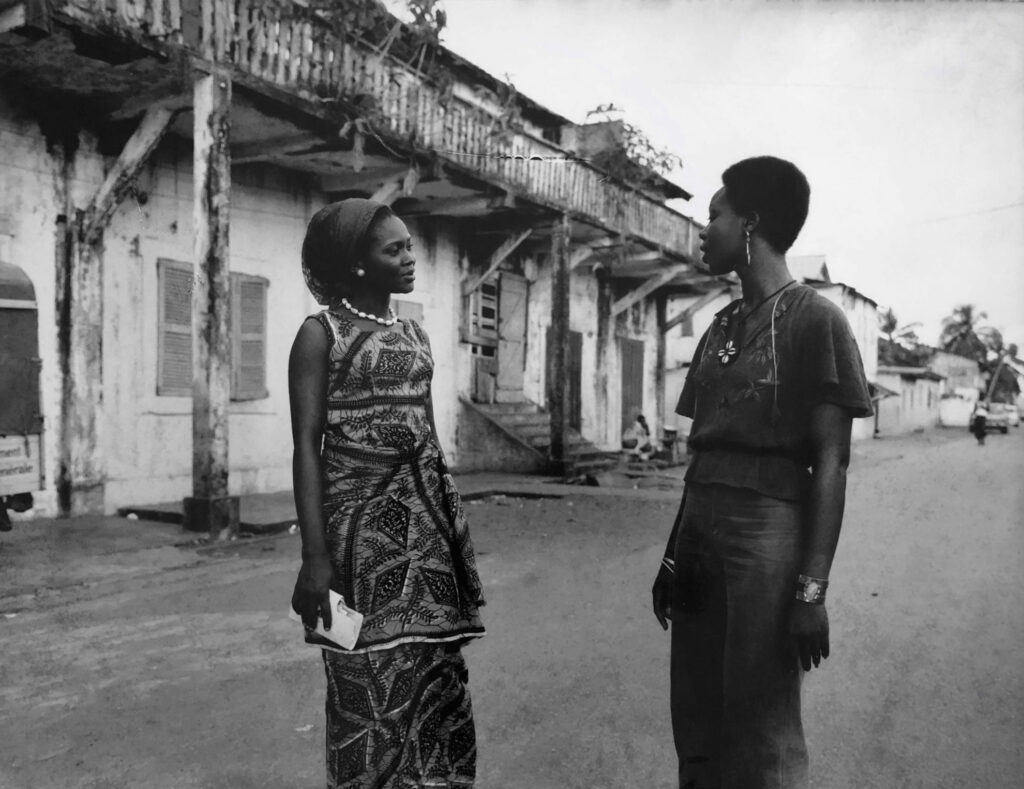

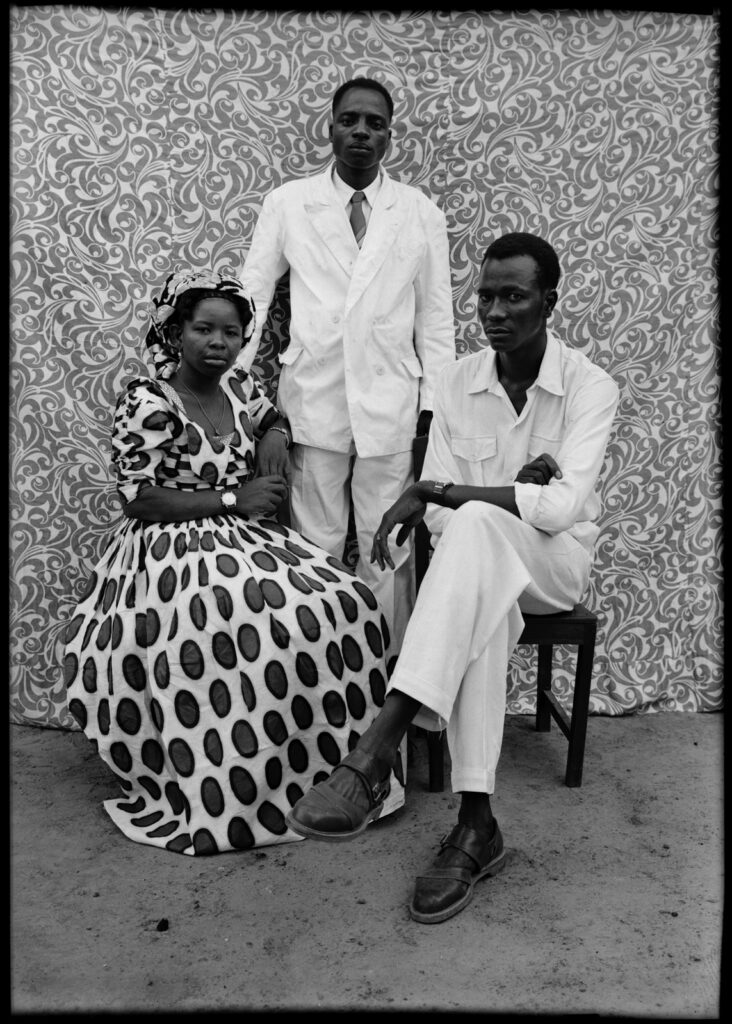

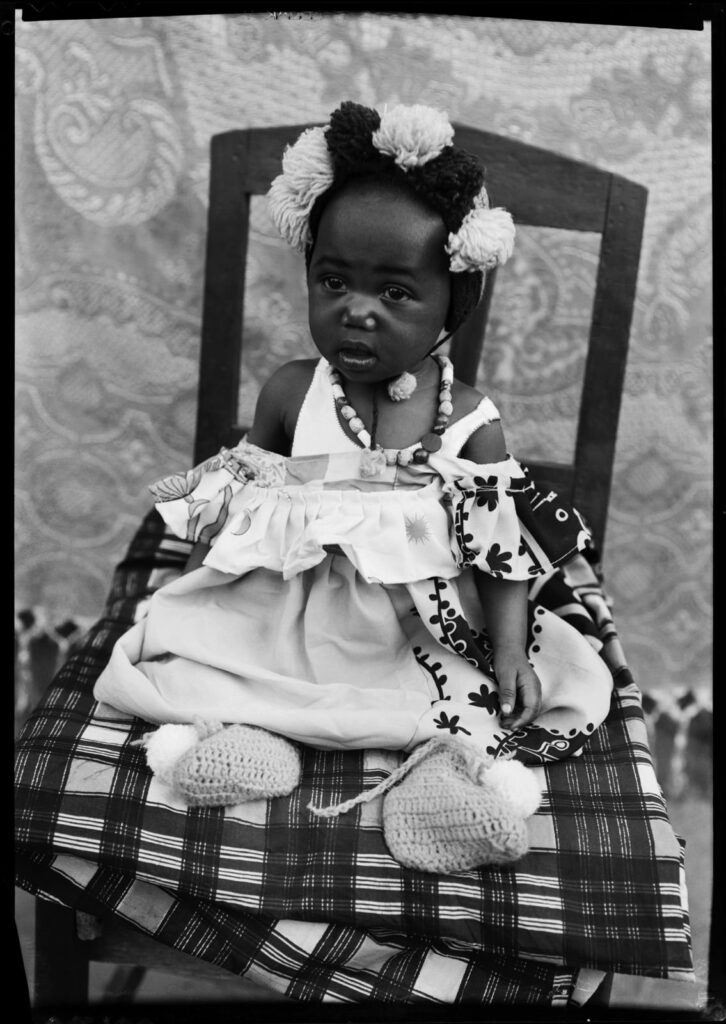

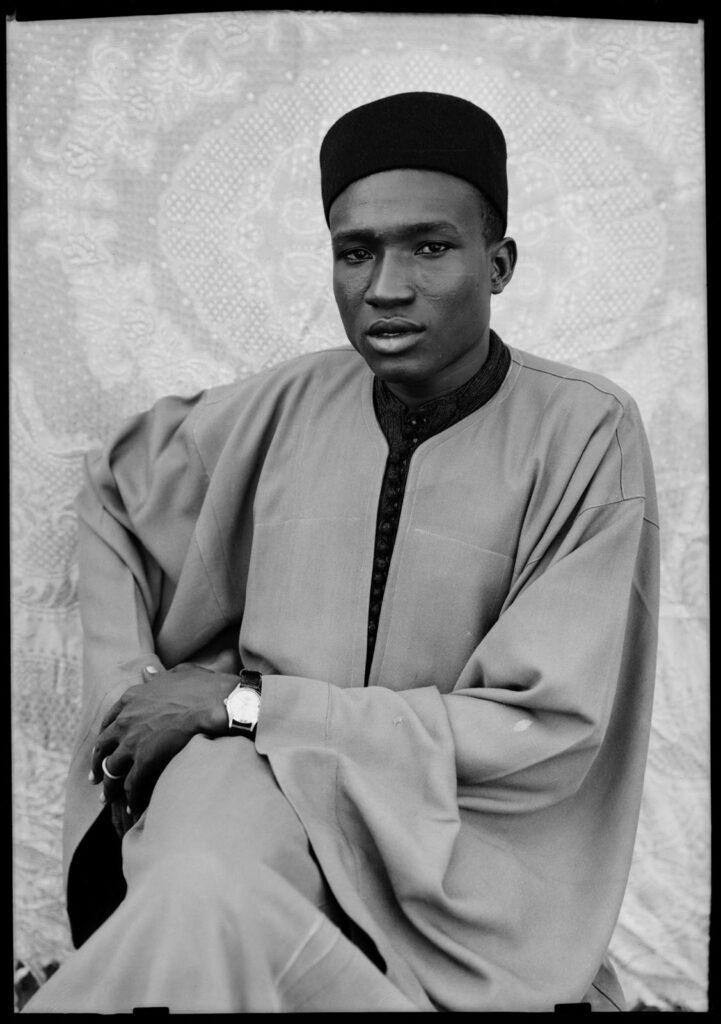

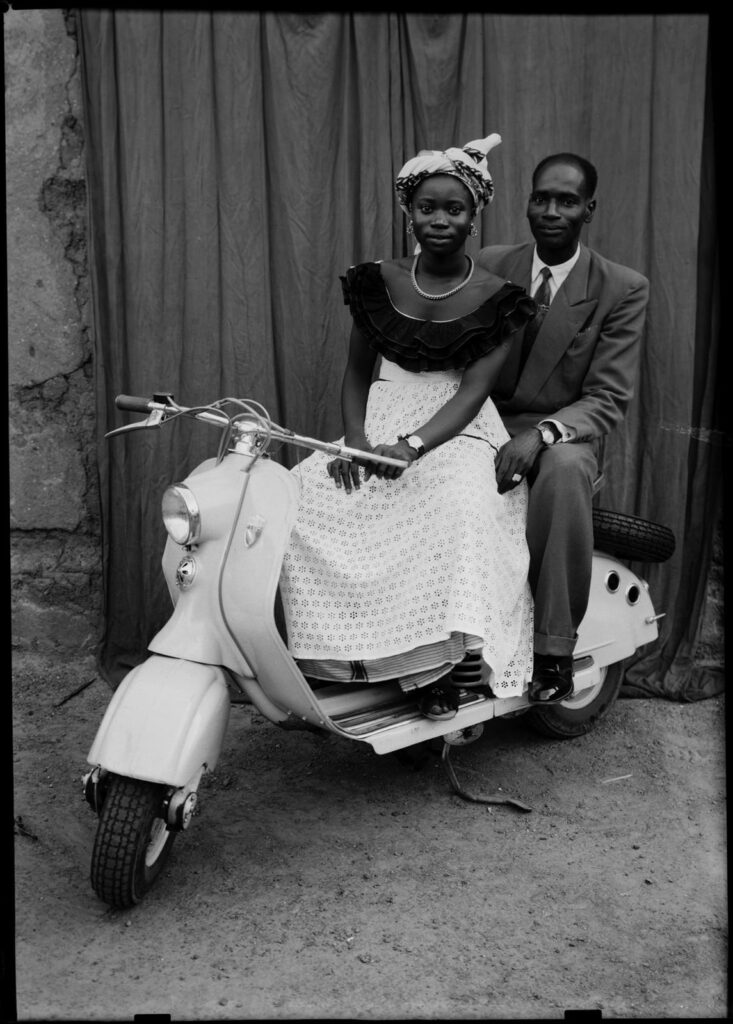

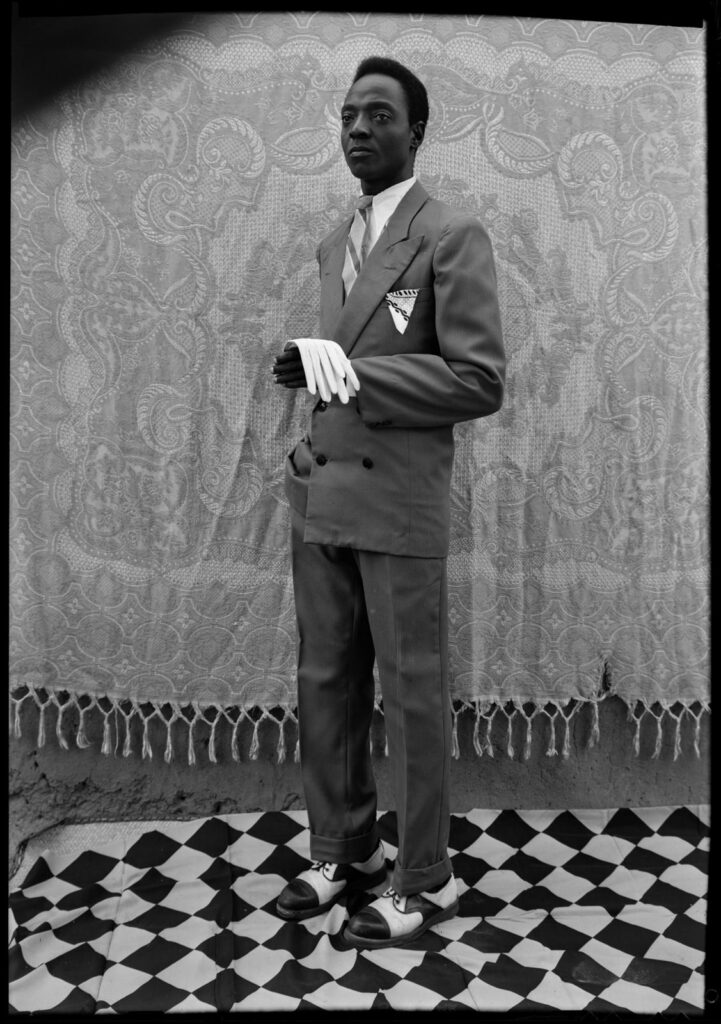

Born in 1980, Diabaté grew up in a city steeped in artistic heritage. She lived in close proximity to Seydou Keïta, the legendary Malian photographer whose elegant portraits captured the essence of post-colonial West Africa. Unbeknownst to her then, those images, along with the works of Malick Sidibé, Samuel Fosso, and Oumar Ly, were shaping her creative identity. Their ability to immortalize moments, celebrate identity, and construct narratives beyond words laid the foundation for her own artistic awakening.

Her formal journey into photography began in 2002 when she enrolled at the Centre de Formation de la Photographie in Bamako. Here, she honed her technical skills, later refining them through internships in Switzerland and France. But it was her ability to infuse emotion and cultural depth into her work that would set her apart.

A Lens Rooted in Heritage and Innovation

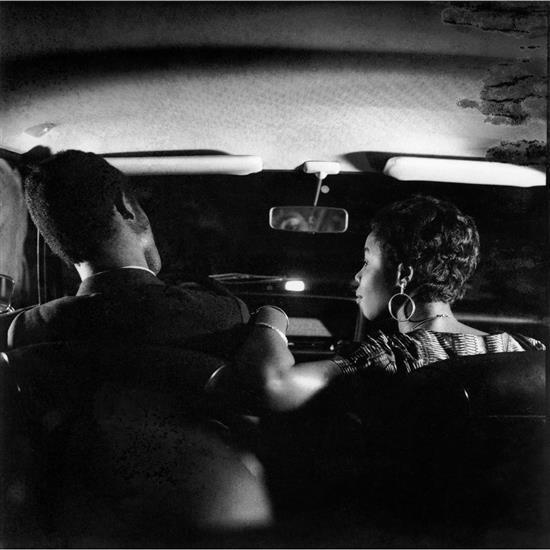

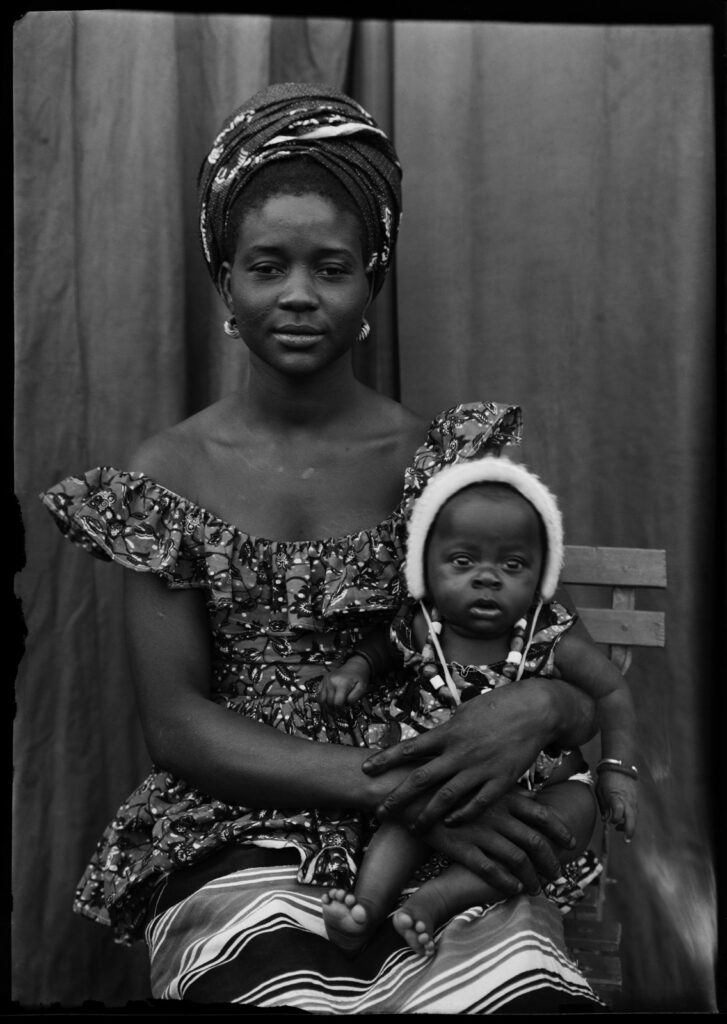

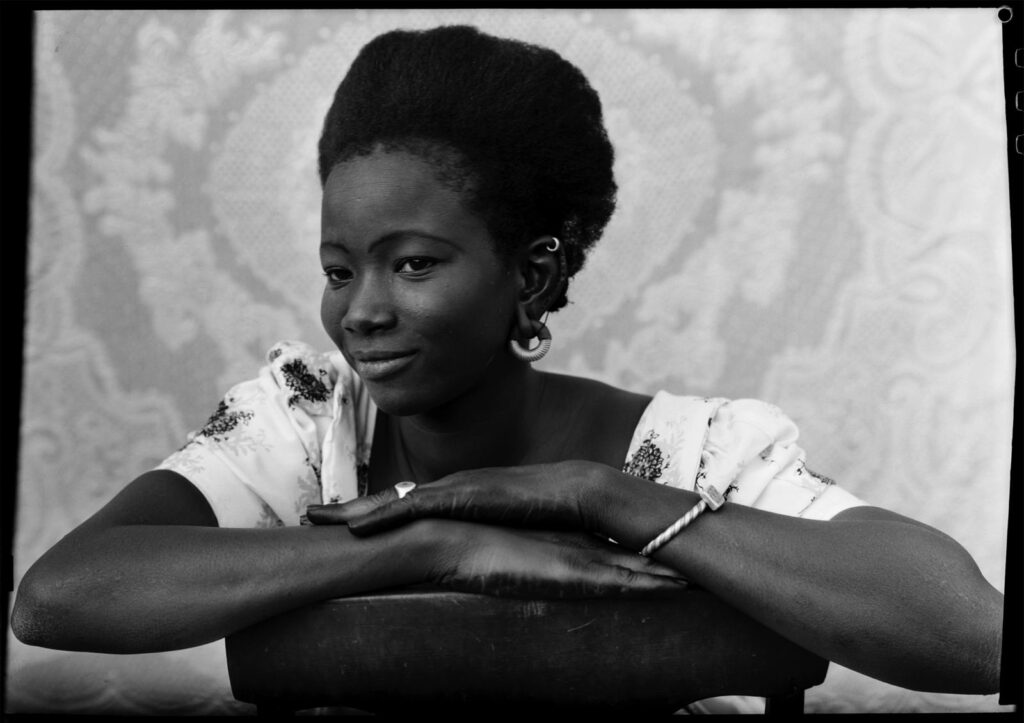

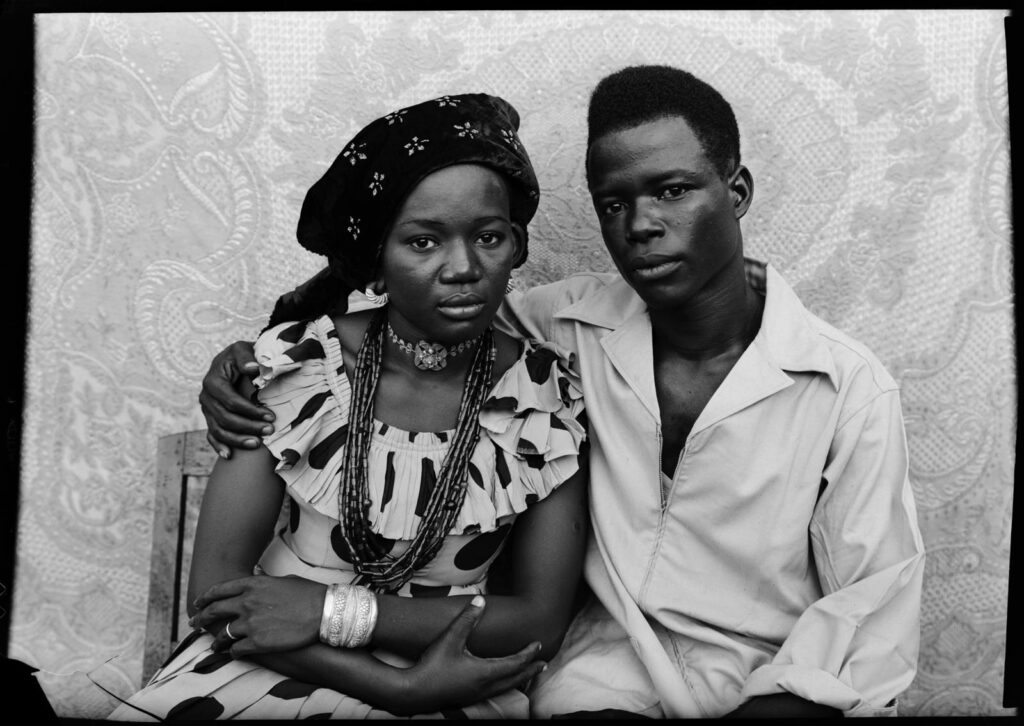

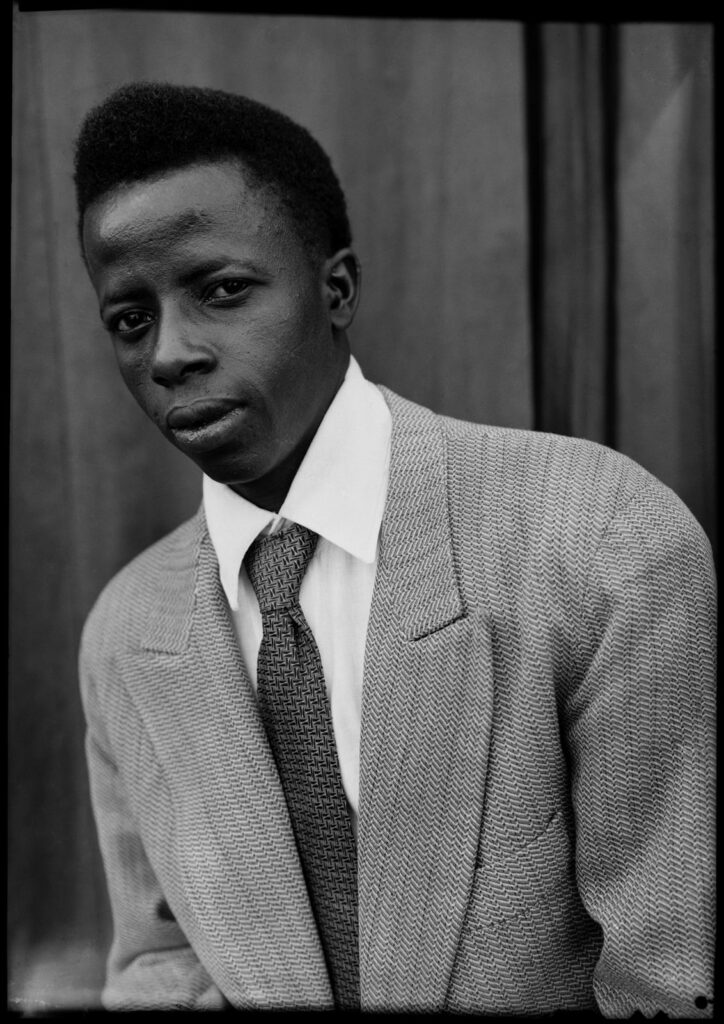

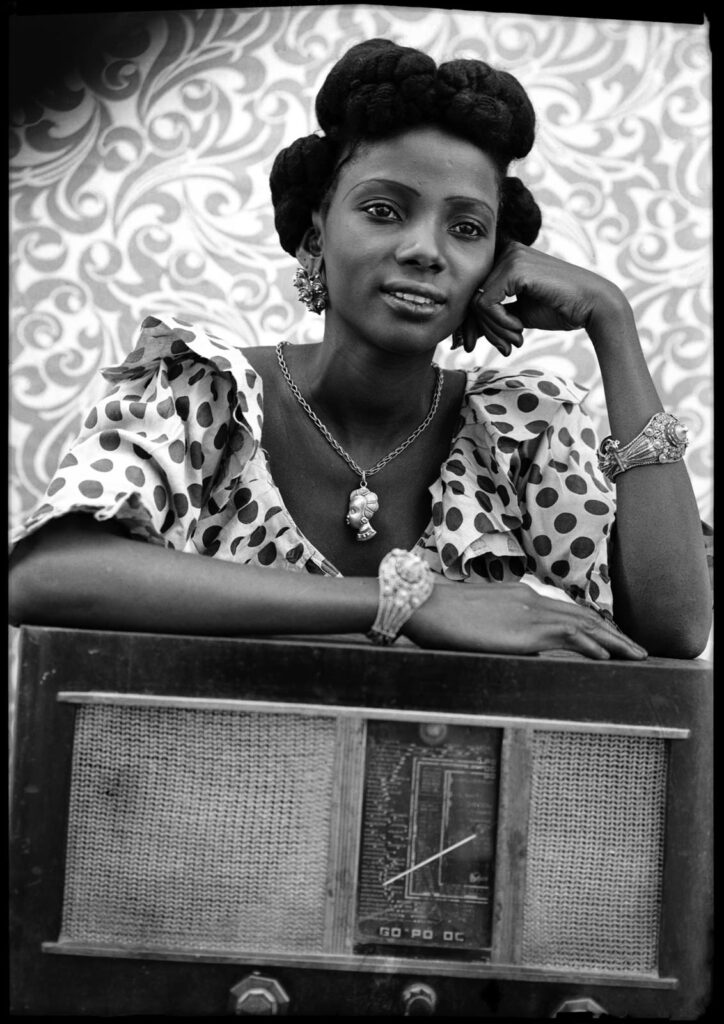

Diabaté’s work straddles tradition and modernity, blending the rich oral storytelling of Mali with the evocative power of the photograph. Her images are not just pictures; they are stories frozen in time, narratives that echo across generations. She has mastered both digital and analog photography, often favoring film for its warmth and texture. Her compositions are intimate, her lighting intentional, and her subjects full of life.

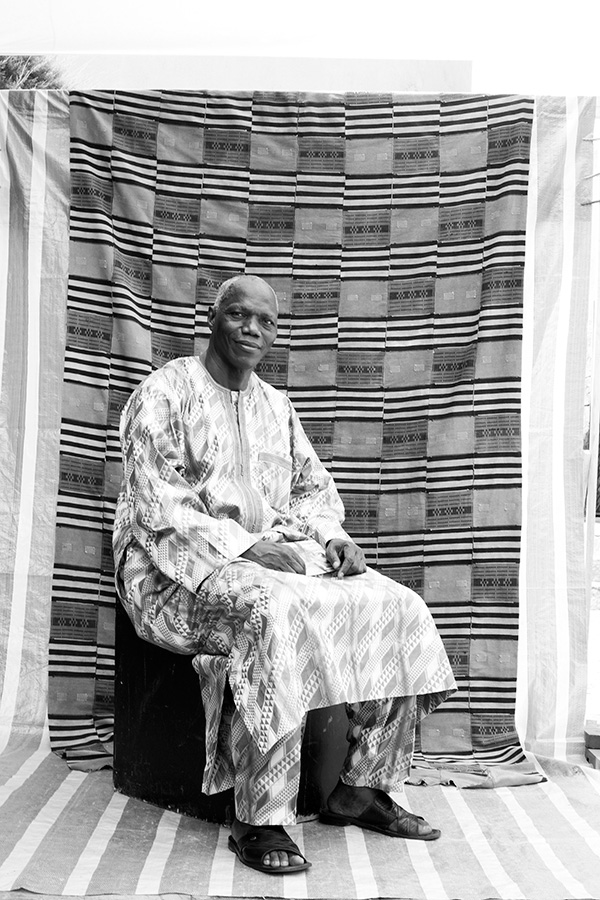

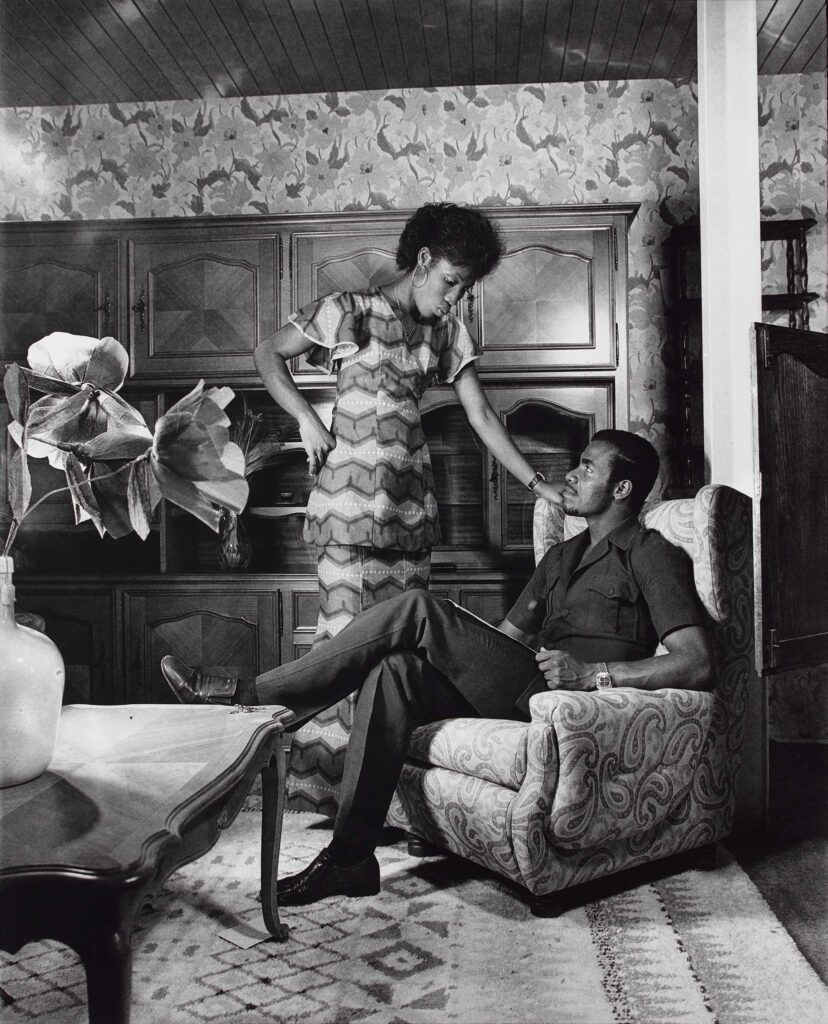

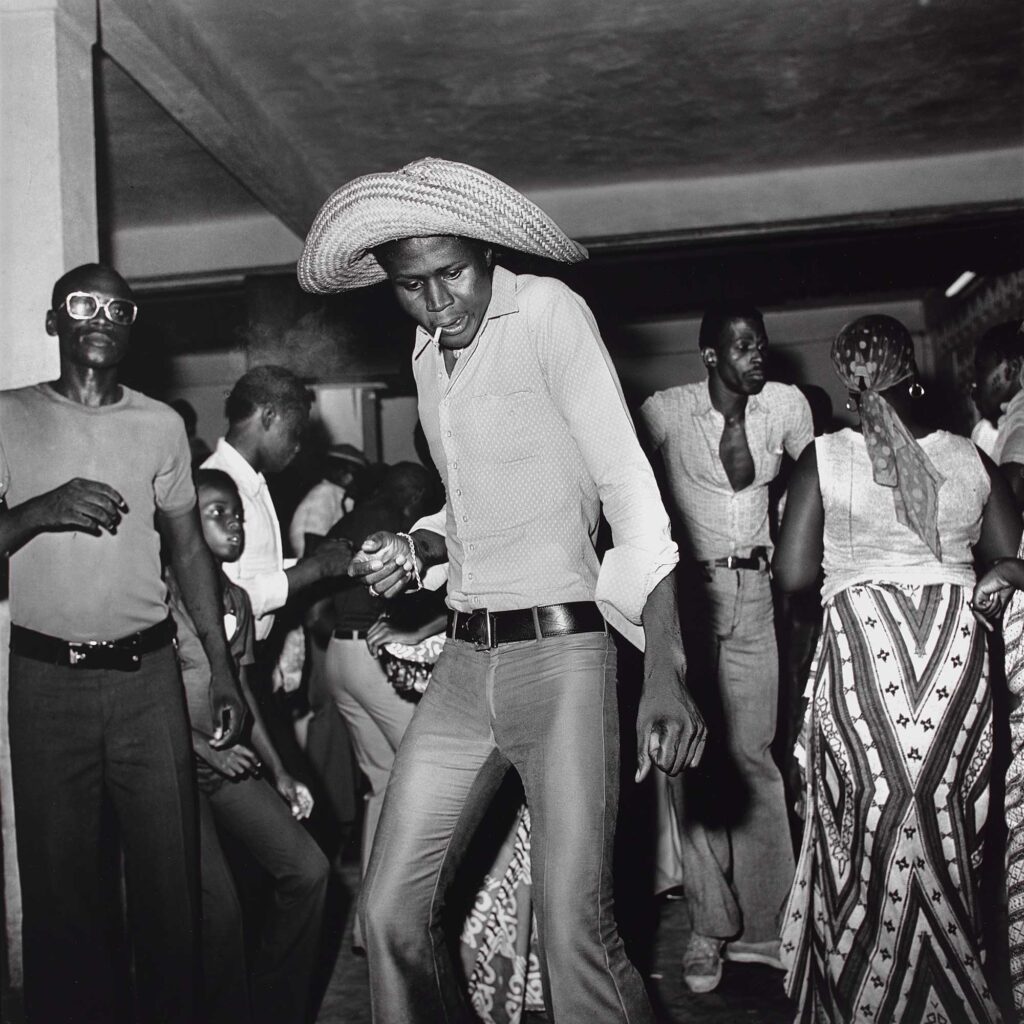

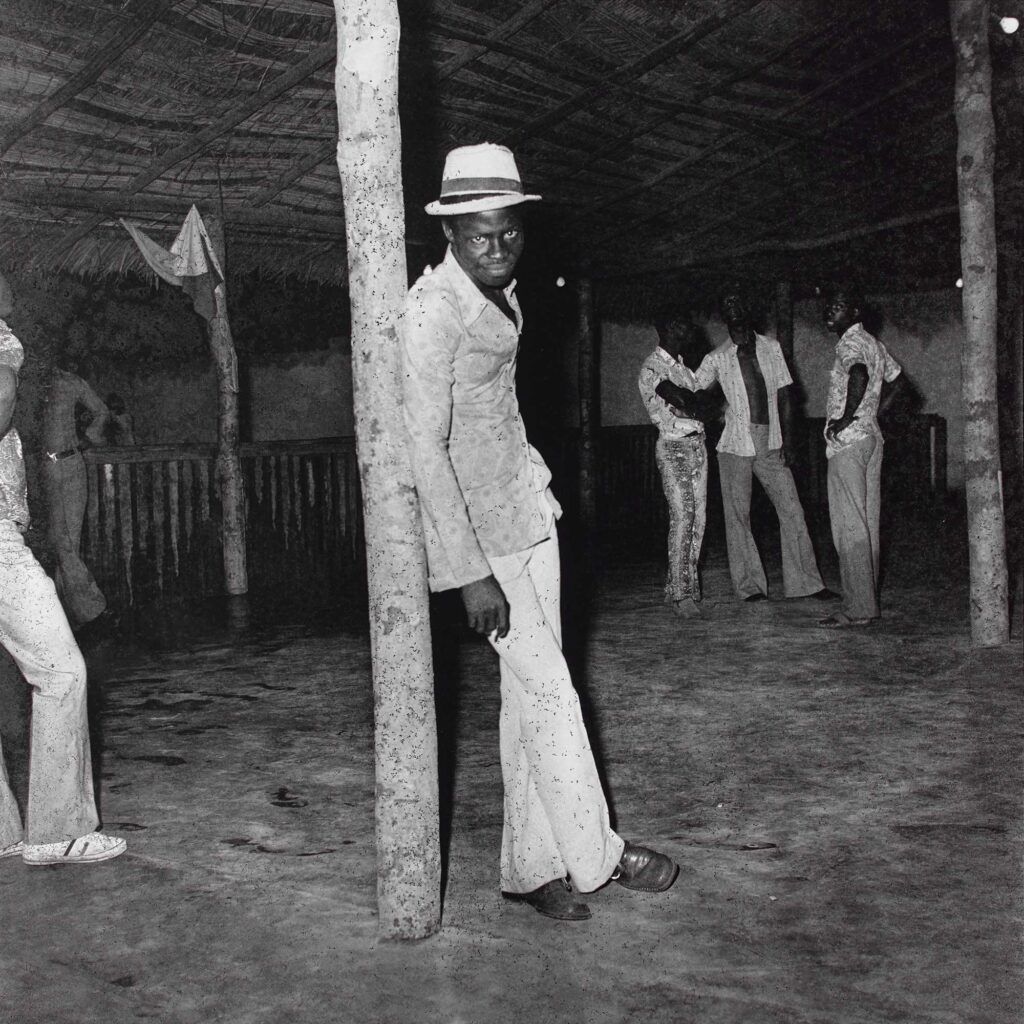

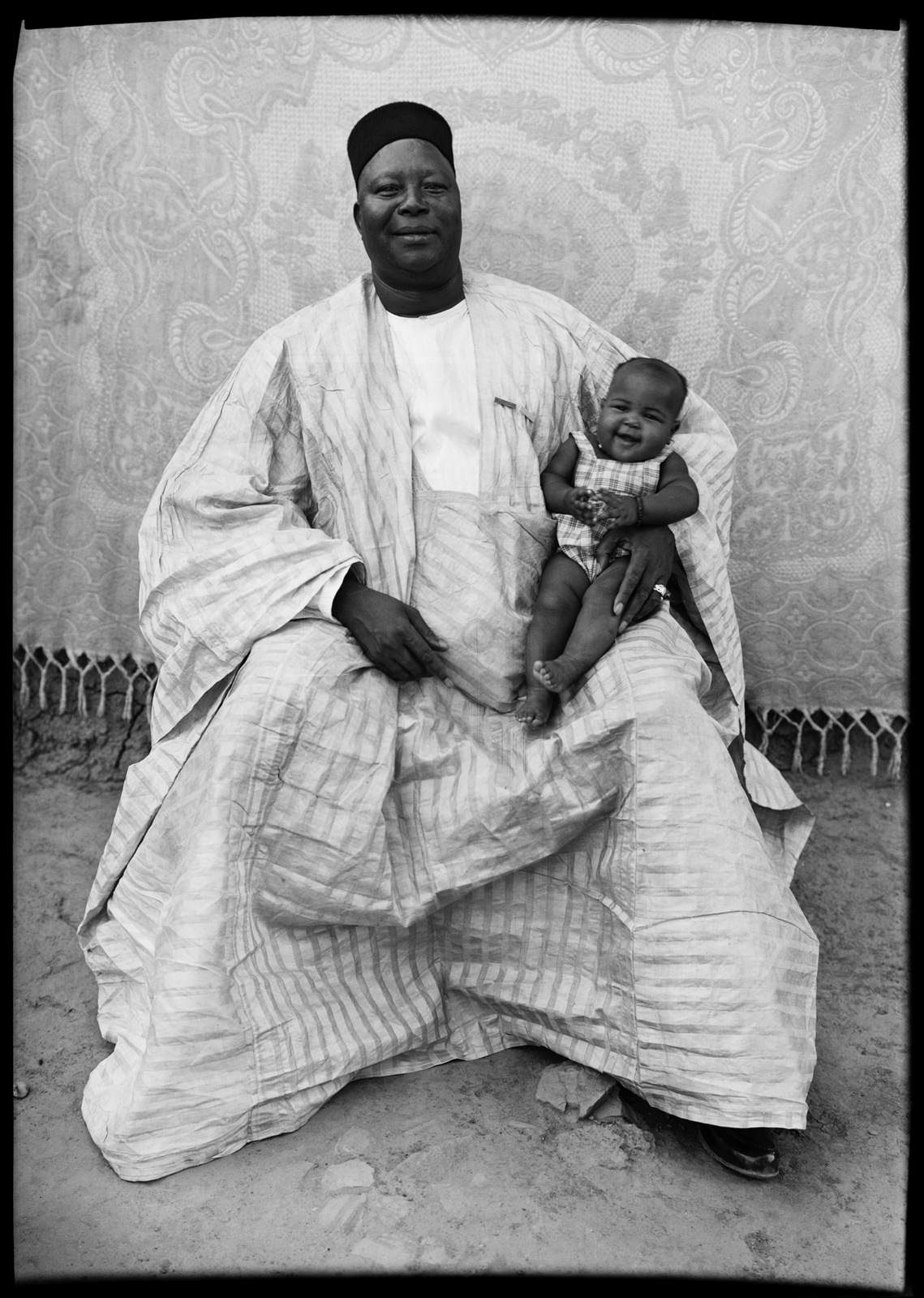

One of her most renowned projects, “Studio Photo de la Rue,” is a tribute to the golden age of Malian studio photography. With a mobile studio, she recreates the iconic staged portraits of Keïta and Sidibé, allowing everyday people to see themselves through the lens of history. The project is both nostalgic and innovative, a time capsule that bridges past and present.

Themes That Resonate Beyond Borders

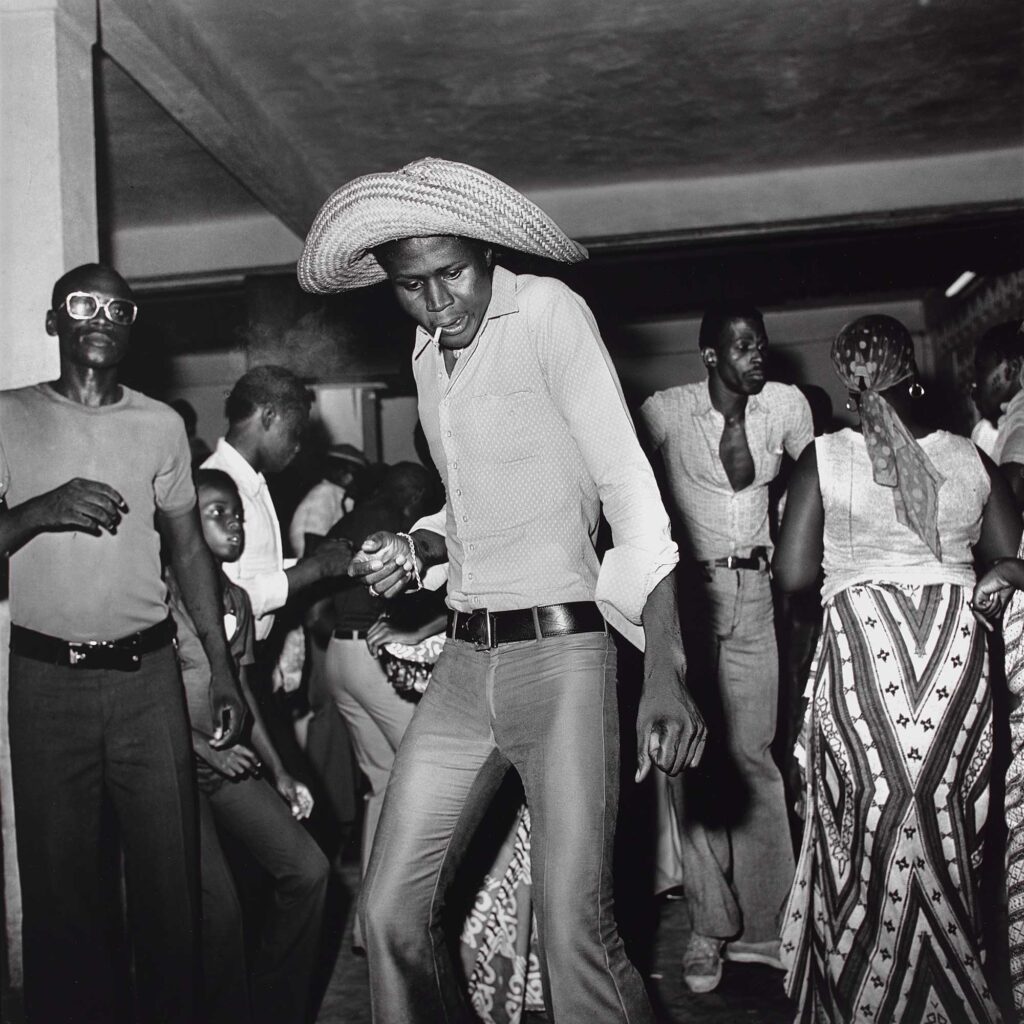

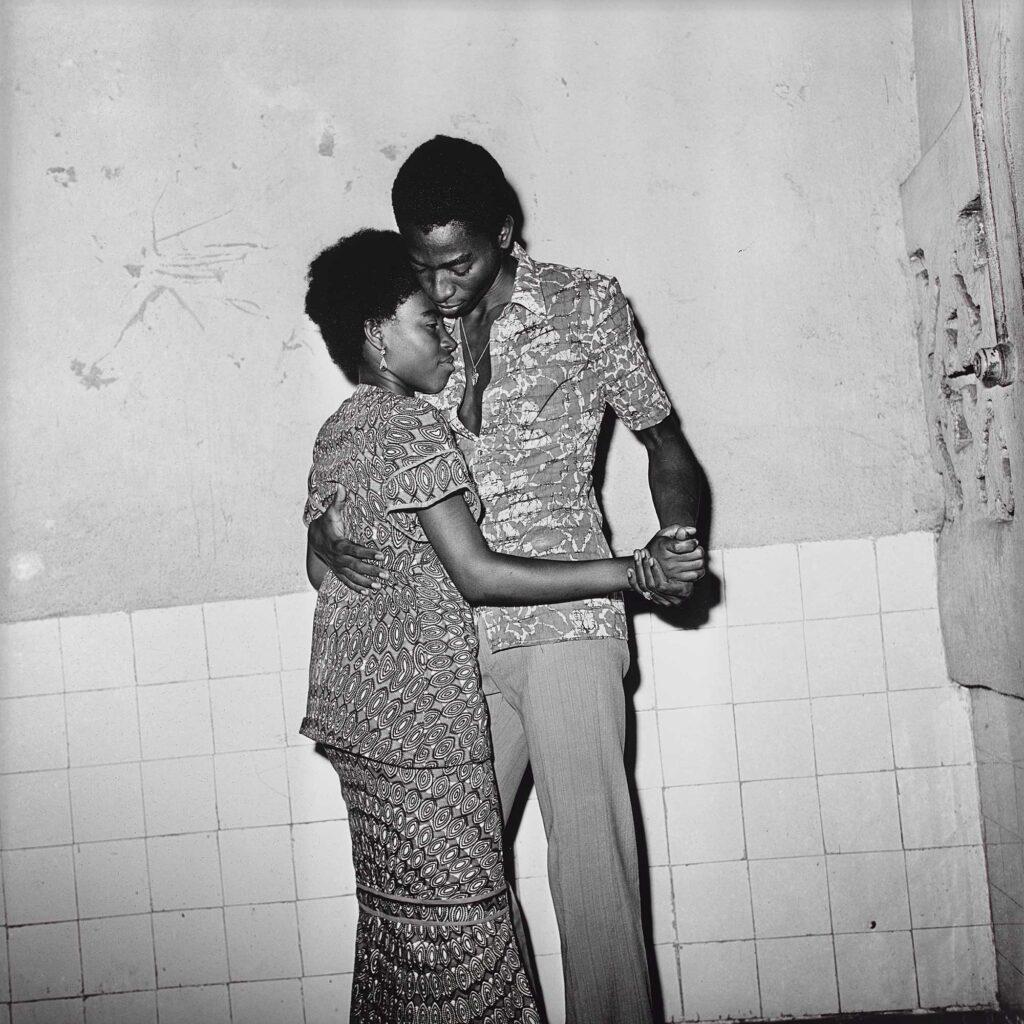

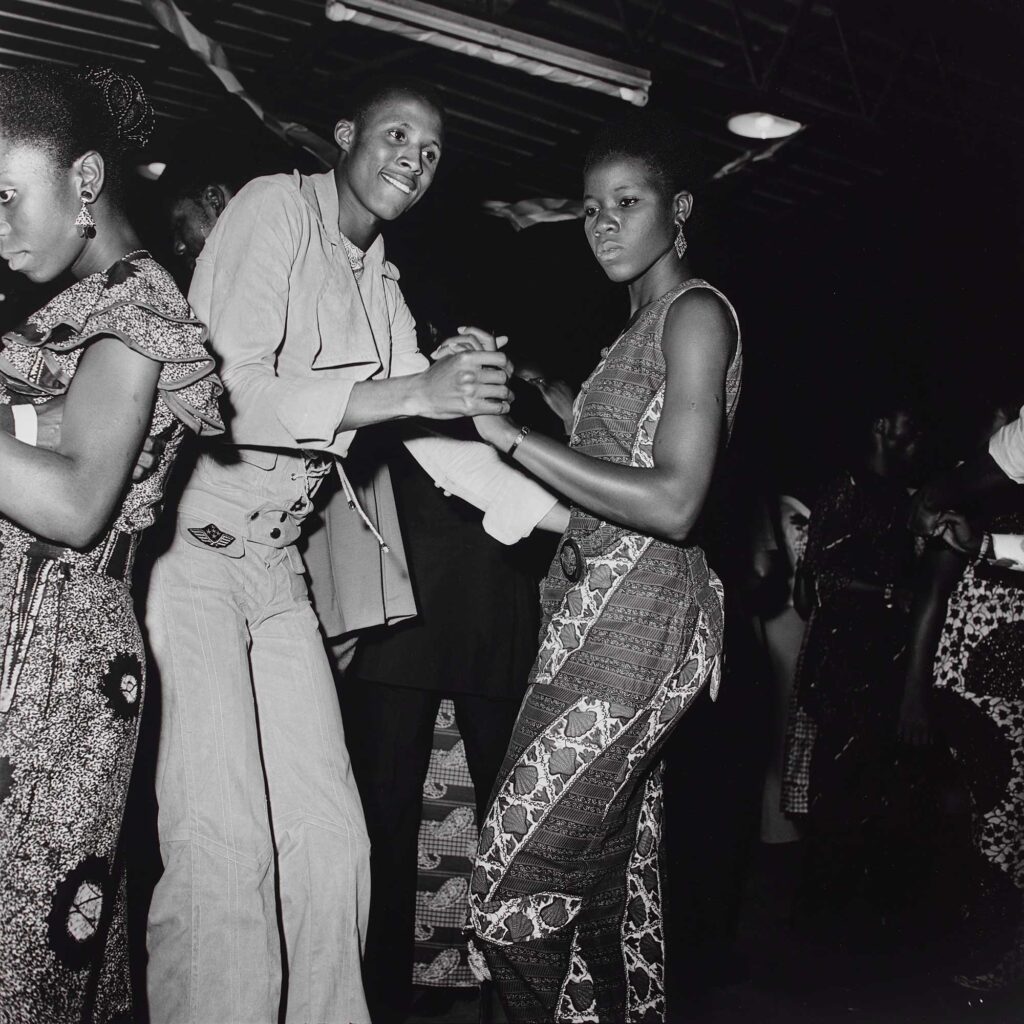

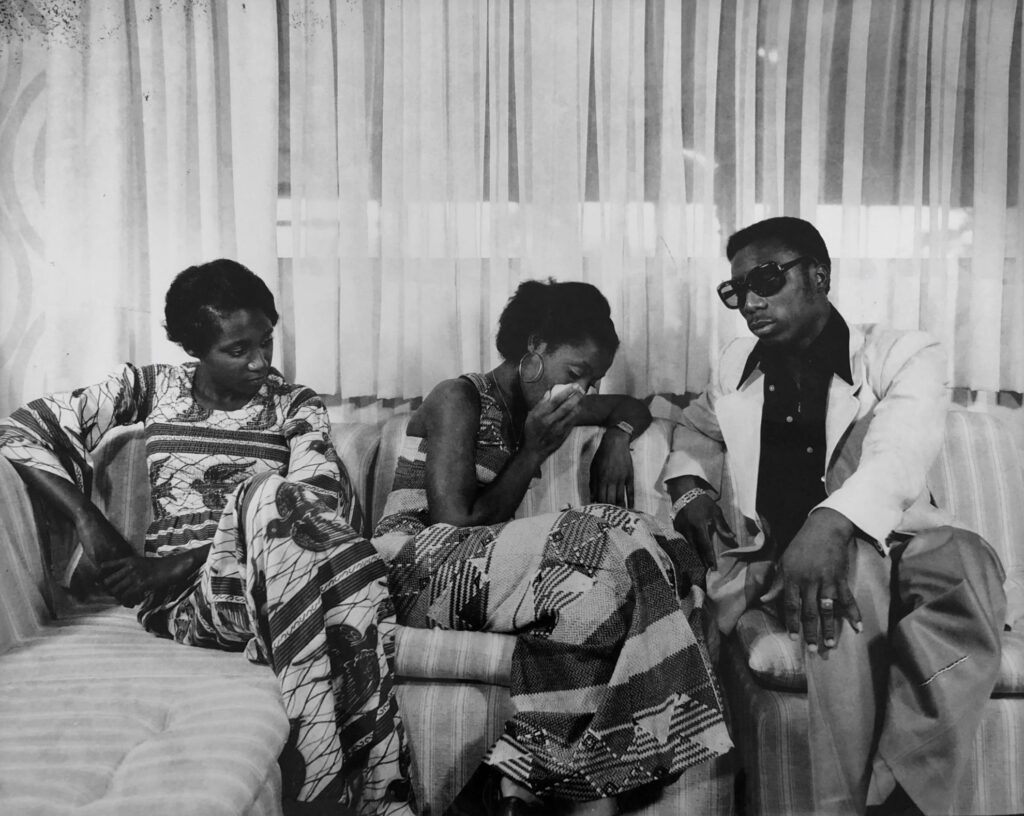

Diabaté’s photography explores deep and universal themes: identity, cultural preservation, youth, and the invisibility of marginalized communities. In “Sutigi” (The Night is Ours), she delves into Bamako’s nightlife, capturing the energy and aspirations of Malian youth. “Héritiers de l’oralité” (Heirs of Orality) pays homage to Mali’s storytelling traditions, visually preserving what has been passed down through spoken word. Meanwhile, “Les Invisibles” (The Invisible Ones) highlights the struggles of those often overlooked, shedding light on the human condition with empathy and dignity.

Beyond portraiture, her work frequently incorporates symbolic elements. Series like “Caméléon” and “L’homme en objet” explore the concept of masks, transformation, and identity, themes deeply rooted in African traditions. Through these projects, she invites viewers to question perception, representation, and the evolving nature of selfhood.

Breaking Barriers, Building Bridges

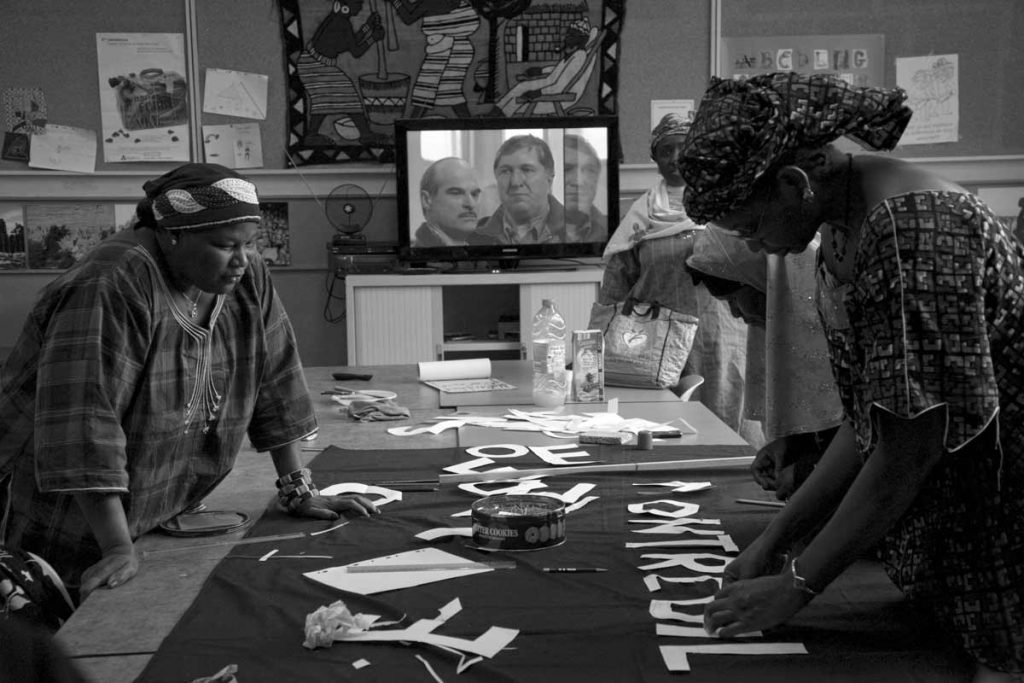

Diabaté is one of the few professional female photographers in Mali, navigating a field traditionally dominated by men. She has not only carved out her own space but has also become a beacon of inspiration for a new generation of African women photographers. Her work with organizations such as Oxfam, the World Press Photo Foundation, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation further showcases her ability to merge documentary storytelling with fine art.

Her talent has earned her international recognition, with exhibitions at prestigious photography festivals such as the Rencontres de Bamako, Les Rencontres d’Arles, and La Gacilly Photo Festival in France. She has received numerous accolades, including the Afrique en Créations prize from the Institut Français, solidifying her reputation as a visual griot of her time.

The Future Through Her Lens

For Diabaté, photography is more than an art form; it is a means of preserving history, empowering communities, and challenging societal norms. She continues to push boundaries with projects that celebrate African identity while engaging with global dialogues on representation and culture.

As she reinvents studio photography for a new era, her mobile studio remains an open stage for anyone willing to step into history. With each frame she captures, she invites us all to see ourselves—not just as we are, but as we wish to be remembered.

Fatoumata Diabaté is not just a photographer. She is a storyteller, a preserver of heritage, and a visionary who reminds us that the camera is more than a tool—it is a voice. And through her lens, Mali, Africa, and the world continue to tell their stories, one photograph at a time.