Reviving the Father of Ivorian Photography

In a forgotten cabin tucked away in the forested heart of Elubo, Ghana, a pivotal moment in history quietly unfolds. There, in the midst of dust, dirt, and the remnants of time, lie the photographs of Paul Kodjo—fragments of a legacy once in danger of vanishing into the void. The images, once bright with life, are now fragile, deteriorating beneath layers of neglect. It’s here that Kodjo’s work is rediscovered, offering a glimpse into the world of an artist who captured the pulse of a nation in transition. This moment, though quietly monumental, is not just about the salvation of his photographs—it’s about the resurgence of an entire cultural and visual history.

Through the dedication of Ananias Léki Dago, a fellow photographer who committed himself to restoring Kodjo’s lost works, the world is now able to witness the impact of a visionary who chronicled the birth of post-colonial Ivory Coast. Léki’s work in reviving Kodjo’s archives is not just an artistic gesture—it’s a political one, a testament to the power of African artists fighting for the preservation of their own stories and legacies. The rediscovery of Kodjo’s work marks a new chapter in the narrative of Ivorian photography, reminding us of the depth and complexity of African visual culture.

A Youthful Lens Opens

Born in 1939 in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, Paul Kodjo’s early life unfolded against a backdrop of seismic change. As independence movements gained momentum across Africa, a new sense of identity began to take root in his homeland. The winds of change stirred not only the political landscape but the creative heart of a young Kodjo, who would soon embark on a photographic journey that would capture the essence of a country reborn. From a tender age, Kodjo’s eyes were attuned to the shifts in his environment, the rise of a new national consciousness, and the aspiration that defined his generation.

Ghanaian Influences and Parisian Inspirations

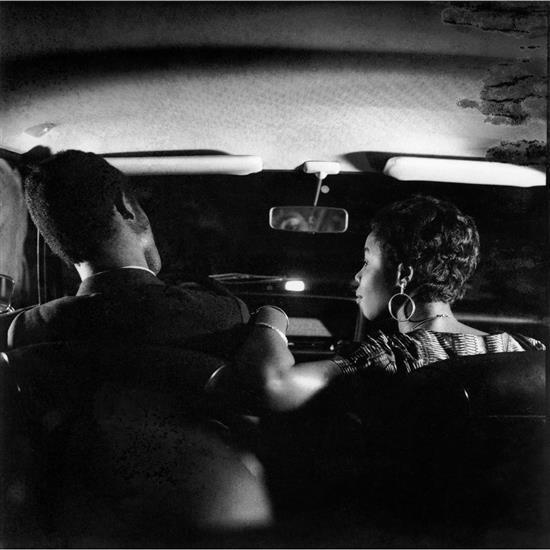

Kodjo’s path led him from Ivory Coast to neighboring Ghana, where he first encountered the power of the camera to document the world around him. His early experiences in Ghana laid the foundation for his future as a photographer, but it was in Paris, during a time of cultural renaissance, that Kodjo’s artistic vision truly blossomed. In the heart of 1960s Paris, surrounded by a kaleidoscope of European art, culture, and cinema, Kodjo’s work began to take on a distinctly cinematic flair. The city’s creative pulse, coupled with his exposure to filmmaking, would deeply influence his later work. The medium of photography, Kodjo realized, could transcend mere documentation—it could tell stories, evoke emotions, and capture life in motion.

Abidjan’s Chronicler

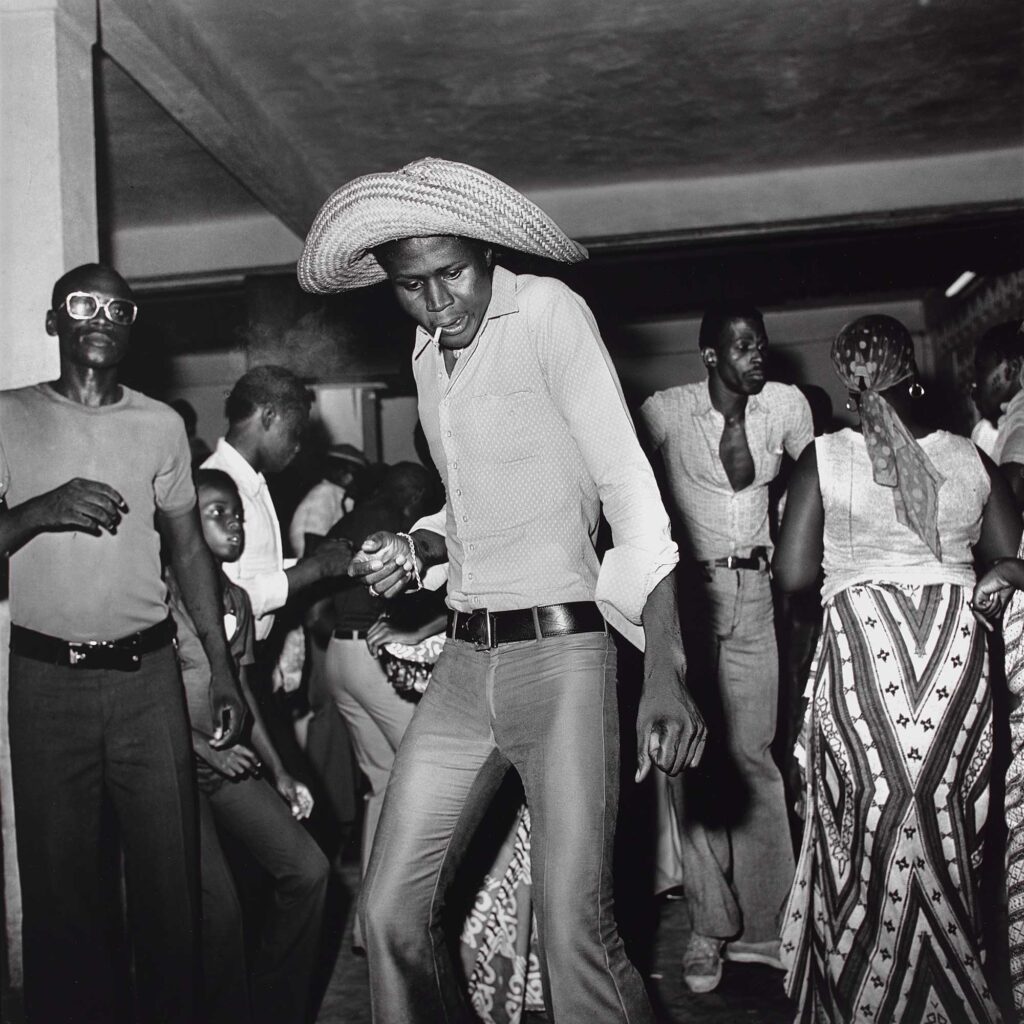

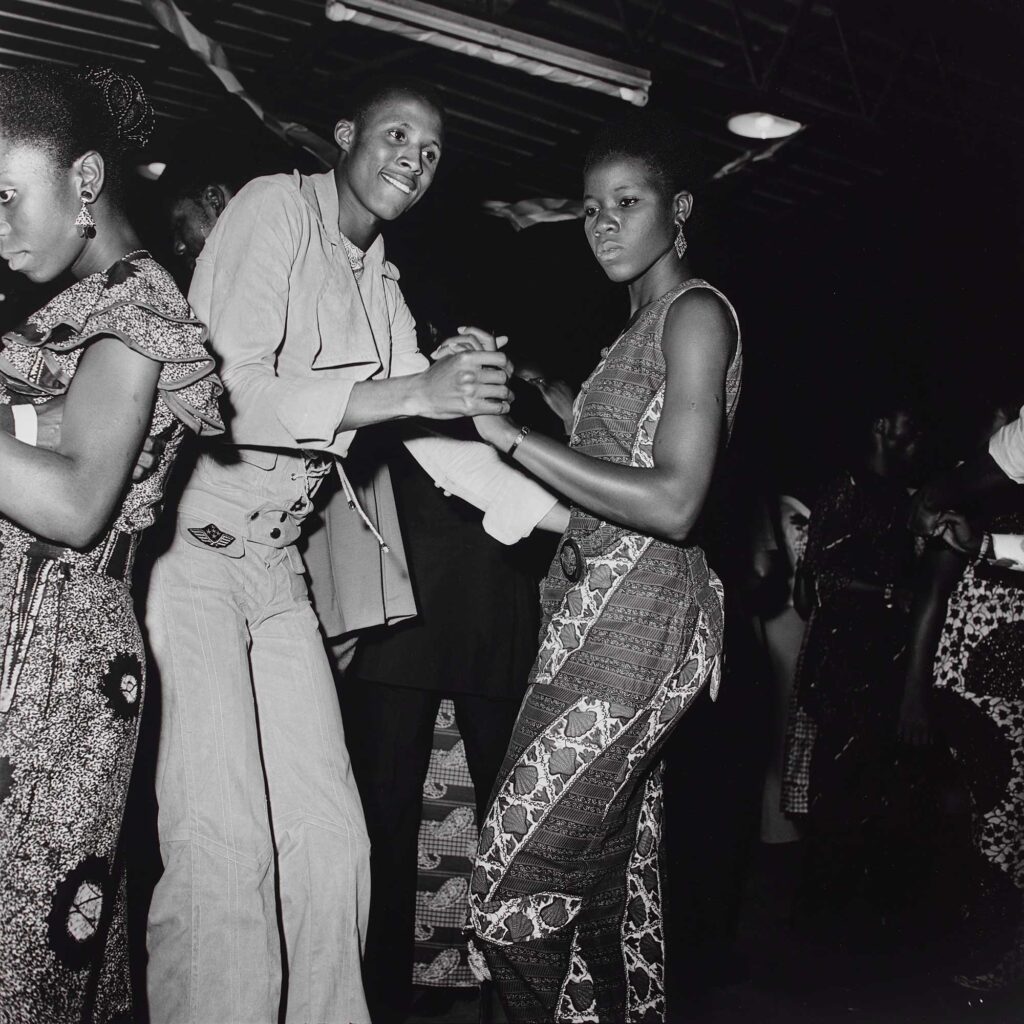

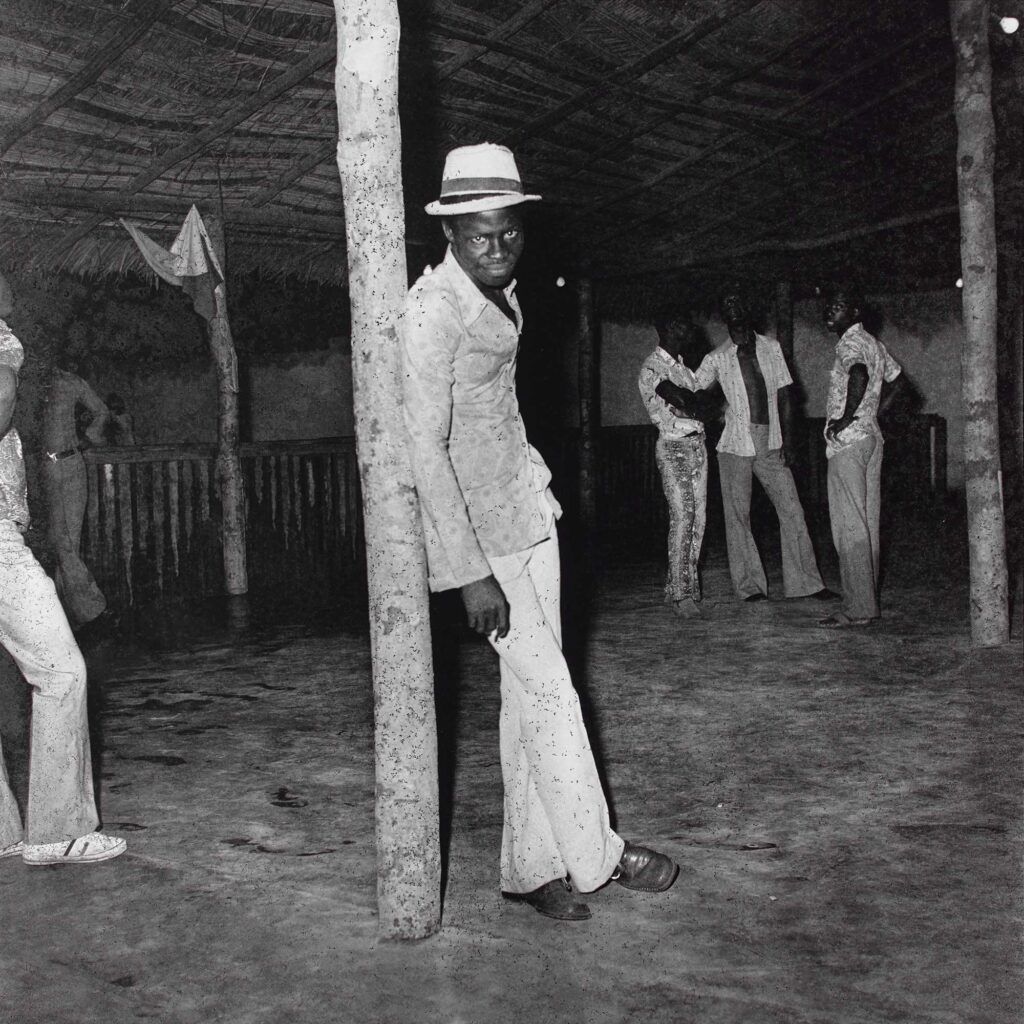

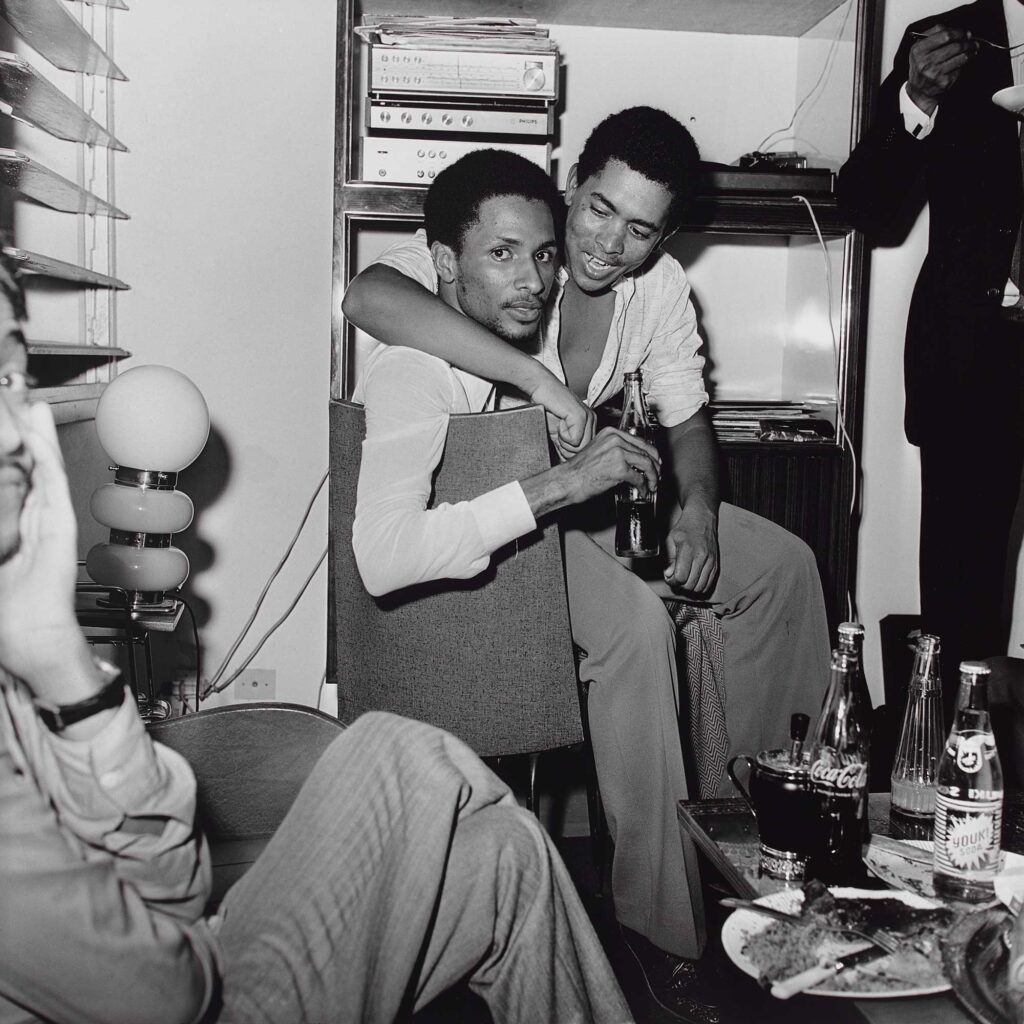

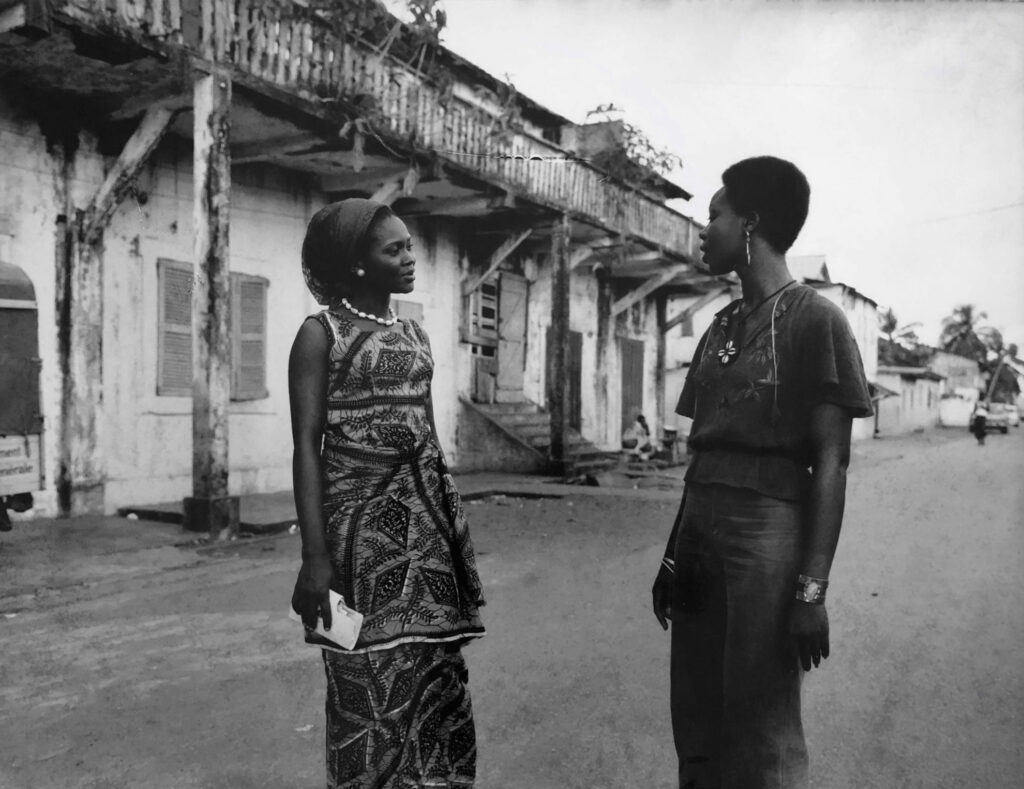

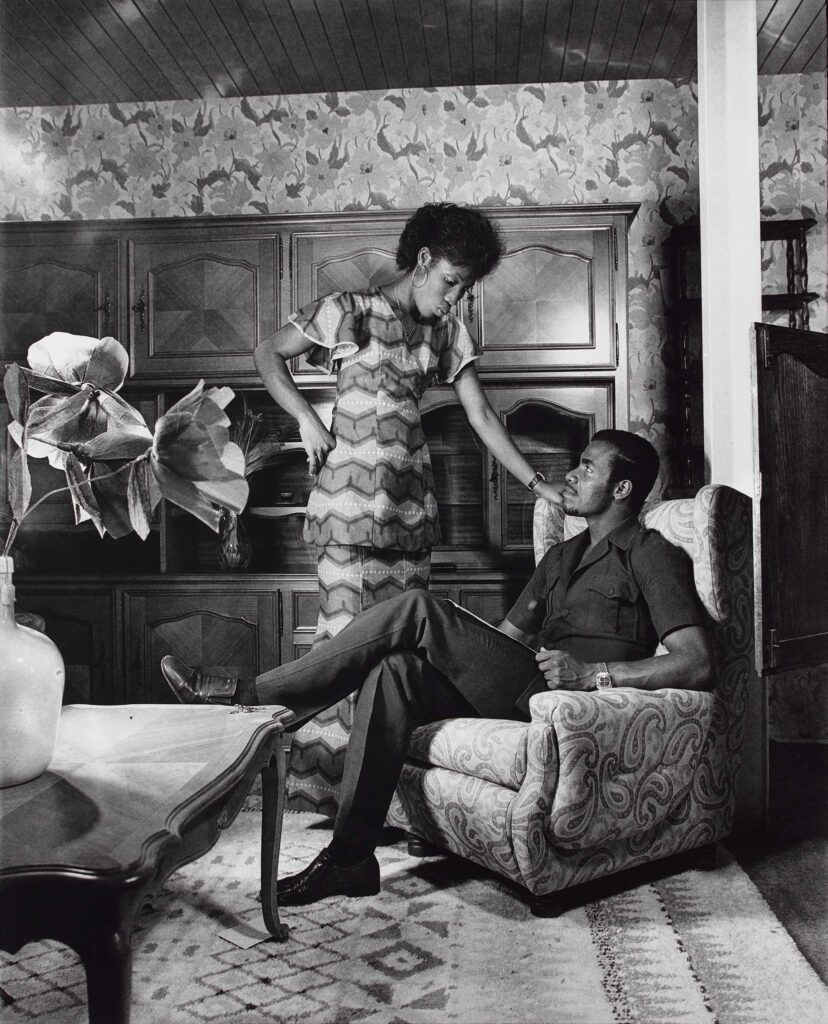

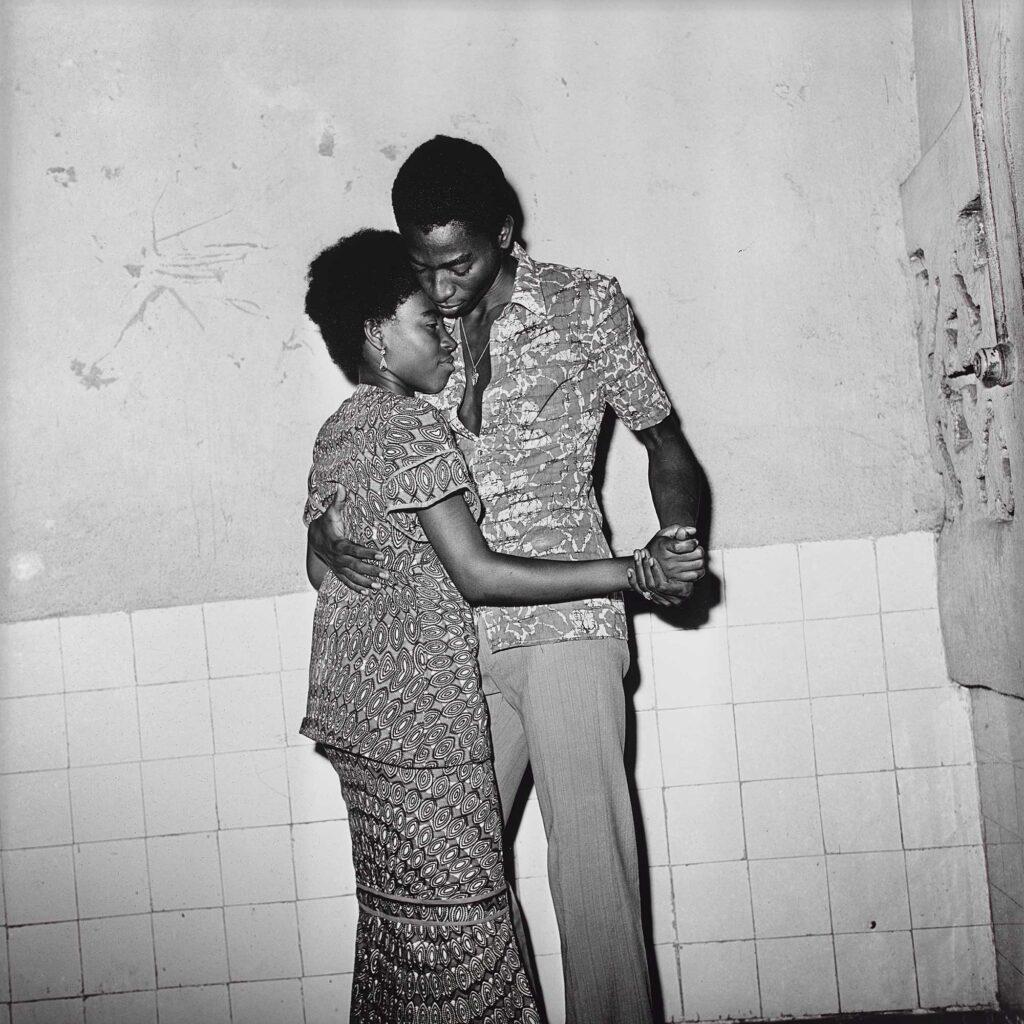

Returning to Abidjan in the 1970s, Kodjo found himself at the center of a rapidly changing city. Abidjan was a city of optimism and promise, its streets alive with energy as Ivory Coast embraced the early days of independence. It was here that Kodjo would truly establish himself as a photographer, capturing the vibrant tapestry of daily life—from bustling markets to the quiet intimacy of human connection. His photographs offered a window into the lived experiences of Ivorians, capturing not just the external landscape but the internal worlds of those he photographed. His street photography became a chronicle of a nation navigating the challenges of independence, offering a visual narrative of aspiration, pride, and the promise of a new beginning.

The Photo-Roman Pioneer

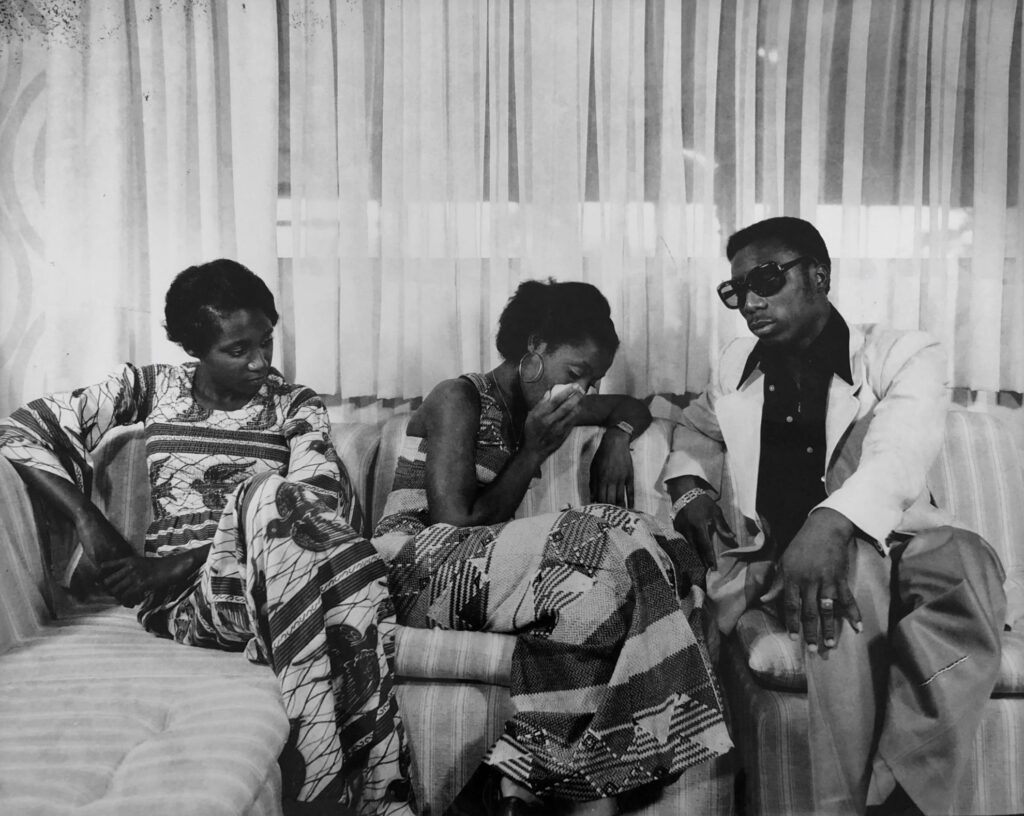

Kodjo’s artistic evolution took a bold turn with his creation of the photo-roman—a groundbreaking genre that combined sequential photography with narrative storytelling. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Kodjo pioneered this format, publishing serialized photographic novels in Ivoire Dimanche, a popular Ivorian magazine. These photo-romans, rich with drama, love, and social intrigue, captivated audiences and showcased Kodjo’s ability to weave cinematic storytelling into still images. The format was a perfect marriage of Kodjo’s dual passions for photography and filmmaking, allowing him to capture the unfolding stories of Ivorian life while pushing the boundaries of what photography could achieve as a narrative art form.

A Rediscovered Legacy

Though Kodjo’s work was largely forgotten after he stepped away from photography in the 1990s, his legacy has undergone a remarkable revival in recent years. As Léki continued his efforts to restore and promote Kodjo’s photographs, the world began to rediscover the powerful images that had once captured the hopes, dreams, and struggles of a nation in the throes of change. Kodjo’s work, though often overlooked, is now hailed as a cornerstone of Ivorian visual culture. His photographs, imbued with a unique cinematic quality, continue to resonate with audiences around the world, capturing not just the history of a country but the human spirit at its most raw and authentic.

A Legacy Resurrected

Kodjo’s story is not just one of personal triumph; it is a testament to the resilience of African artists in the face of historical erasure. His photographs, with their deep empathy for his subjects, their cinematic flair, and their social commentary, stand as a powerful reminder of the importance of preserving Black archives. Through his lens, Kodjo captured more than moments—he captured the essence of a country and a people at a pivotal moment in history. His work is not just a reflection of the past; it is a living document that continues to shape the present, offering a profound commentary on identity, aspiration, and the complexities of post-colonial Africa.

Today, as the “father of Ivorian photography,” Kodjo’s legacy stands as a beacon of hope for the future of African photography. His work serves as a reminder that even in the face of adversity, the stories of African artists—like Kodjo’s—can and must be preserved, honored, and shared with the world. Through his photographs, Kodjo not only documented a moment in history but also gave future generations the gift of seeing themselves through their own eyes.