Malick Sidibé: The Eye That Captured Mali’s Soul

Malick Sidibé saw the world in black and white, but his images were anything but monochrome. Each frame he developed held a universe of emotion, energy, and life, turning fleeting moments into eternal stories. He was not just a photographer; he was a storyteller, a visual historian, and an artist whose lens chronicled the rise of a new Mali—one that was vibrant, youthful, and pulsating with rhythm.

The Shepherd’s Journey

The name Malick Sidibé conjures images of joyous youth, vibrant music, and the pulse of 1960s Bamako. But who was the man behind the lens? Born in the village of Soloba, 300 km from Bamako, in Mali, in either 1935 or 1936, Sidibé’s journey began far from the neon glow of Bamako’s dance floors. His father, Kolo Barry Sidibé, was a Fula stock breeder, farmer, and skilled hunter who had wished for his son to attend school. Tragically, he passed away before Malick was able to enroll at the age of 16. Despite this, Sidibé’s artistic talent surfaced early, sketching in the dust while tending his flock. His gift did not go unnoticed. Selected to attend a colonial school, his path led him to the École des Artisans Soudanais in Bamako, where his artistic spirit truly blossomed.

The Studio and the City

Fate, it seemed, had a plan for Malick Sidibé. An apprenticeship with the renowned French photographer Gérard Guillat-Guignard (“Gégé la pellicule”) in 1955 opened the door to a world of photographic mastery. Initially tasked with calibrating equipment and delivering prints, Sidibé soon mastered photography, eventually taking on his own clients. But his inspiration wasn’t confined to the studio walls. The streets of Bamako, pulsating with the energy of a newly independent nation, became his muse. In 1957, after Guillat-Guignard closed his studio, Sidibé ventured into the heart of the city, documenting nightlife, sporting events, concerts, and the ever-evolving social dynamics of young people. His lens followed Mali’s youth as they embraced music, dance, and modern fashion, capturing their joyous rebellion and newfound freedom.

A Collaborative Dance

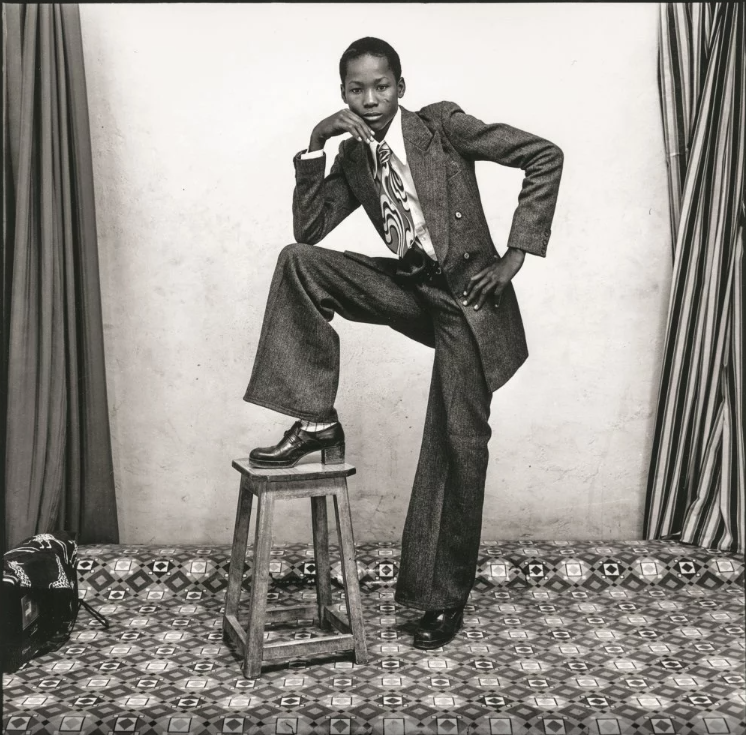

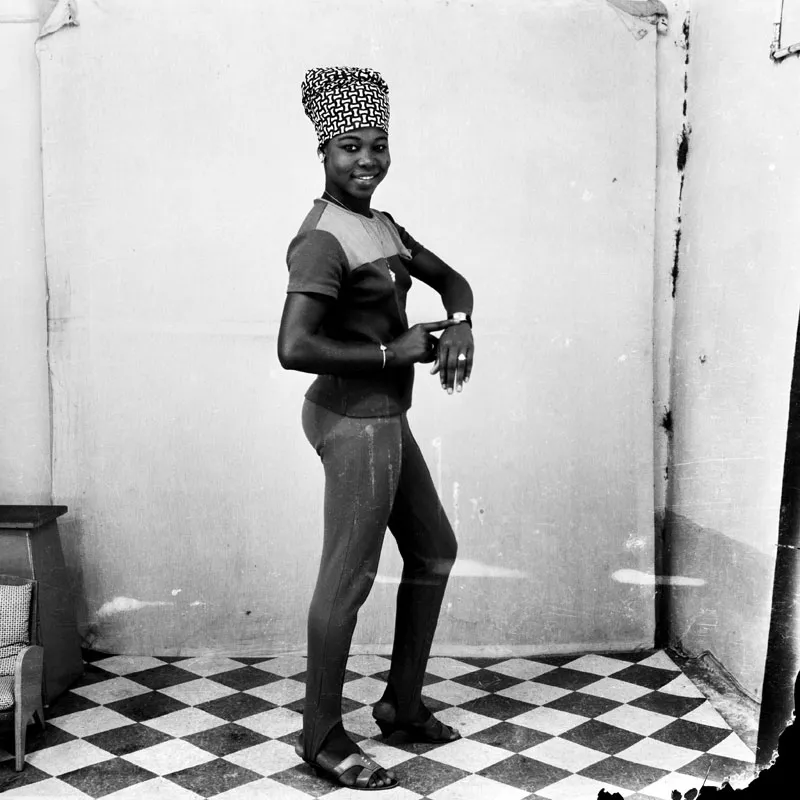

His studio, Studio Malick, which he opened in the Bagadadji neighborhood of Bamako in 1962, became more than just a place for portraits—it was a stage for collaboration and self-expression. Imagine the scene: music spilling onto the streets, laughter echoing through the open door, and Sidibé, with a twinkle in his eye, guiding his subjects through a creative dance. He encouraged them to bring props—a cherished record player, a stylish hat, a bicycle—anything that spoke to their individuality. Young men leaned on motorcycles with a rebel’s ease, couples clung to each other with quiet affection, and women posed with a poise that challenged conventions. His background in drawing proved invaluable: “As a rule, when I was working in the studio, I did a lot of the positioning. As I have a background in drawing, I was able to set up certain positions in my portraits. I didn’t want my subjects to look like mummies. I would give them positions that brought something alive in them.”

Icons and Echoes

Sidibé’s work was more than documentation; it was a celebration. “It’s a world, someone’s face,” Sidibé once mused. “When I capture it, I see the future of the world.” And indeed, through his lens, he revealed Mali’s past, present, and future in a single click of the shutter.

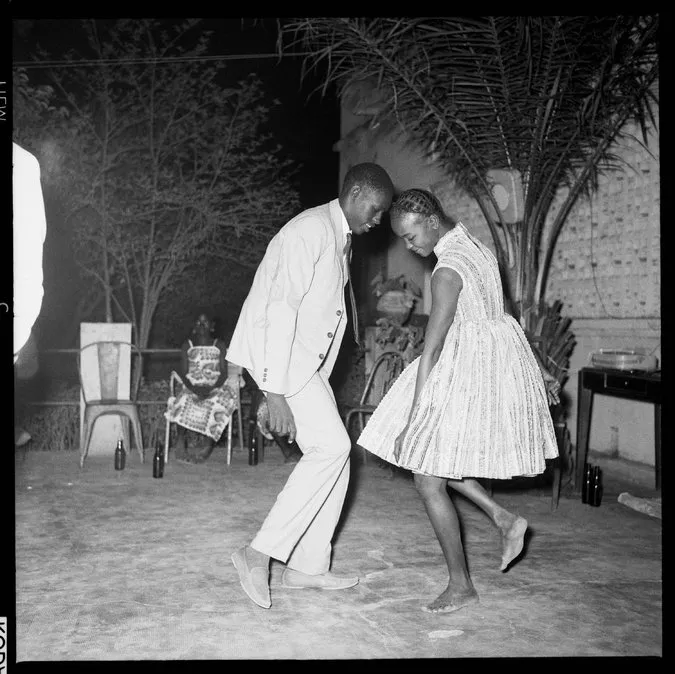

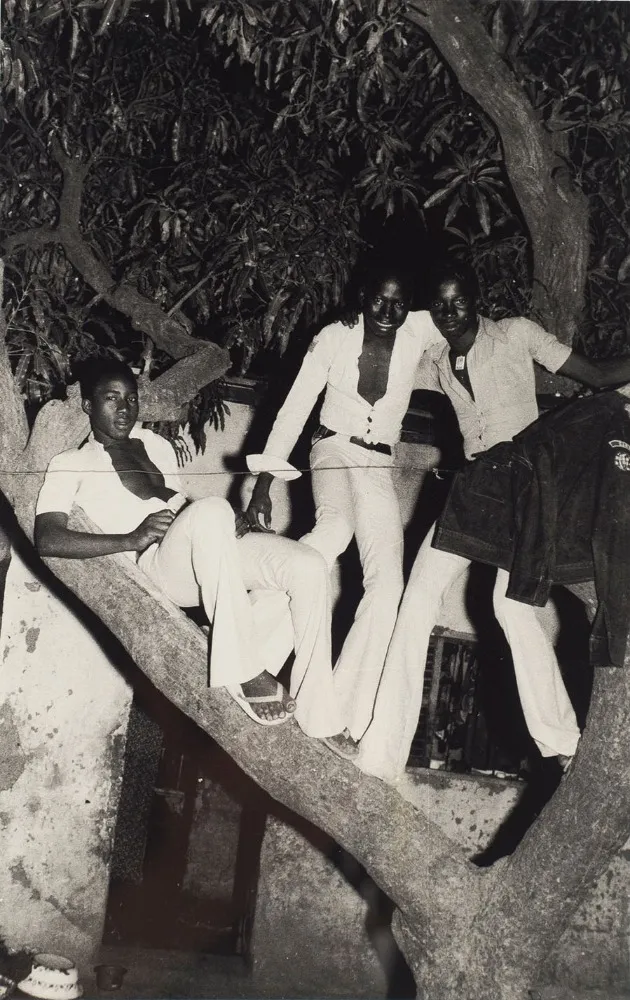

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Sidibé captured the vernaculars of style—brash suits, clashing prints, bold accessories, and traditional elements intertwined with modernity. The party, the club, the dance floor—these were his settings, the spaces where people came to be seen and celebrated. He roamed the city from midnight till dawn, shooting hundreds of frames every weekend, using flash for outdoor shoots and tungsten lighting in his studio. His charm and humor helped put subjects at ease, making his portraits feel natural and alive.

Some of his most iconic images include Nuit de Noël (Happy Club) (1963), depicting a joyous barefoot couple dancing on Christmas Eve, Fans de James Brown (1965), capturing young Malians influenced by global music trends, Jeune Homme avec Radio (1970), symbolizing the era’s technological advancements, and Les Trois Amis (1976), a testament to camaraderie and evolving fashion.

His Works and Publications

Sidibé’s work extended beyond the confines of his studio, finding a permanent place in books, exhibitions, and archives worldwide. His photographs have been featured in numerous publications, celebrating his unique ability to capture the essence of Mali’s cultural evolution. Some of the most notable books include Malick Sidibé: Photographs (2003), Malick Sidibé: Chemises (2007), and Malick Sidibé: Mali Twist (2017), which offer an extensive look at his visual storytelling.

His images have been exhibited across the globe, from the Fondation Cartier in Paris to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. His retrospectives have drawn international acclaim, placing him among the great photographers of the 20th century. His ability to blend documentary realism with artistic composition continues to inspire contemporary photographers and artists alike.

Legacy of Light

In 1976, as Mali’s nightlife scene changed and affordable cameras became more accessible, Sidibé transitioned to primarily shooting studio portraits, ID photos, and repairing cameras. His local fame endured, but it was not until 1994 that his work gained international recognition through French curator André Magnin. One of his most celebrated images, Nuit de Noel, Happy Club (1963), became emblematic of his ability to capture music’s liberating spirit.

Sidibé’s influence extended far beyond photography. His work inspired artists, musicians, and filmmakers alike. Janet Jackson’s 1997 music video Got ’til It’s Gone drew heavily from Sidibé’s aesthetic, paying tribute to his evocative style. Malian musicians such as Salif Keita and Ali Farka Touré rose to international fame around the same time that Sidibé’s work gained global recognition, highlighting a cultural renaissance that echoed across the arts. More recently, Inna Modja’s 2015 video for Tombouctou was filmed in Sidibé’s own studio, cementing his lasting impact.

Even after his passing in 2016 from complications related to diabetes, Sidibé’s photographs continue to resonate. They are reminders of a time when Mali danced to a new beat, when youth dressed not just in fashion but in freedom. His legacy lives on in the eyes of every artist who seeks to tell a story through a lens, in every frame that captures not just an image, but a soul.

Malick Sidibé didn’t just take pictures; he immortalized moments. And in doing so, he ensured that Mali’s golden age of music, dance, and self-expression would never fade into history. His photographs remain, timeless as the light that first illuminated them.

Leave a Reply