Seydou Keïta: The Master of Malian Portraiture and the Father of African Photography

In the heart of Bamako, in 1921, a young boy was born into a family of carpenters. His future seemed set—he would learn the craft of woodworking, just as his father and uncle had before him. But fate had other plans. In 1935, his uncle returned from Senegal with a small gift—a Kodak Brownie camera. It was a modest object, simple in design, yet it held within it the power to change everything. For Seydou Keïta, it was the spark that ignited a lifelong passion, setting him on an extraordinary path that would redefine African portraiture.

A Studio in Bamako: The Birth of an Icon

Keïta was largely self-taught, though he learned the technical aspects of photography from Pierre Garnier, a French photography supplier, and Mountaga Traoré, a fellow photographer. But his true education came from experience—experimenting, perfecting his craft, and discovering his own visual language. In 1948, against the backdrop of a shifting Mali, he opened his first photography studio in Bamako-Koura.

This was more than just a business venture—it was a sanctuary of self-expression. People from all walks of life stepped through his doors, eager to see themselves through his lens. His studio was a bridge between tradition and modernity, where subjects could choose how they wished to be remembered.

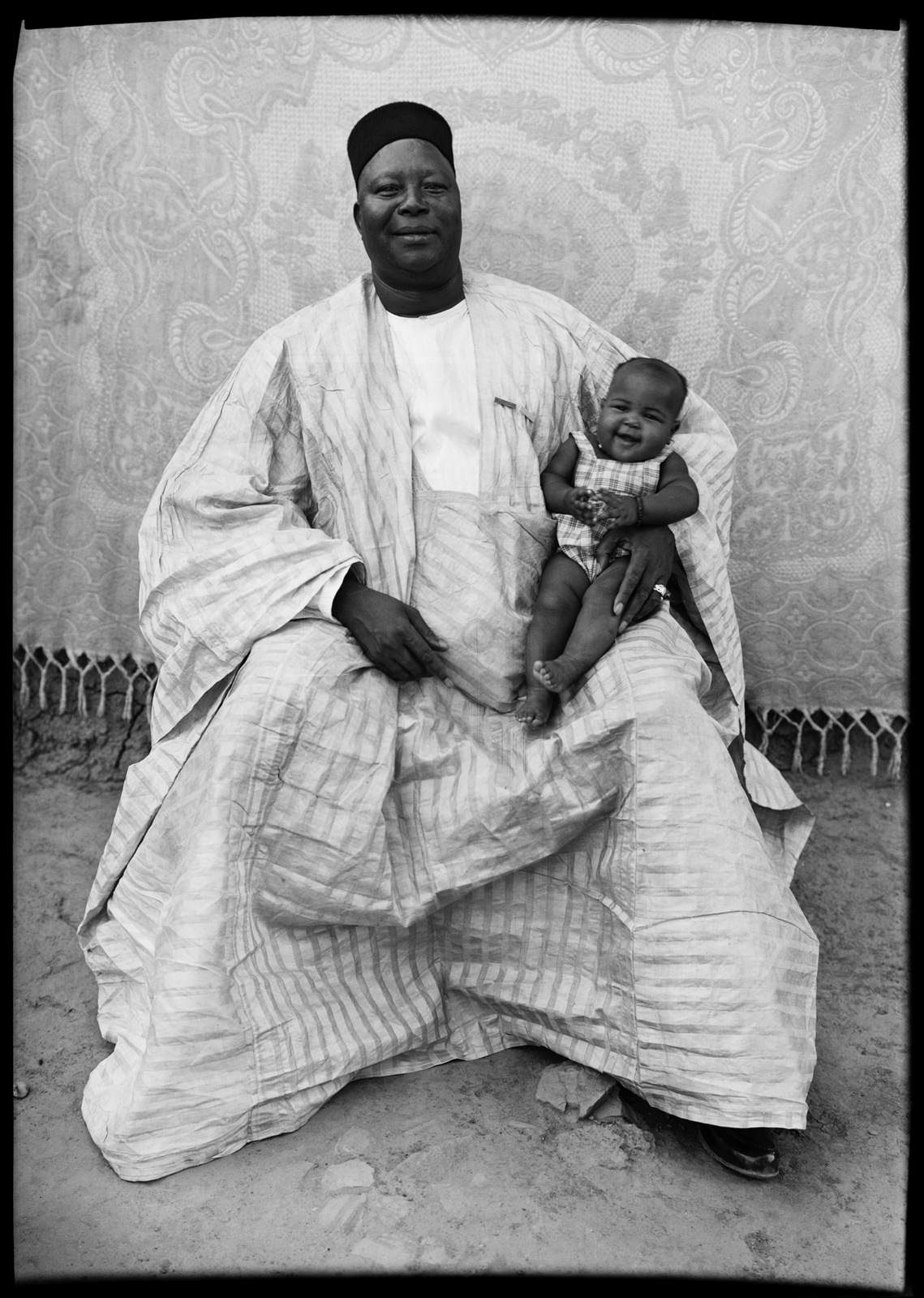

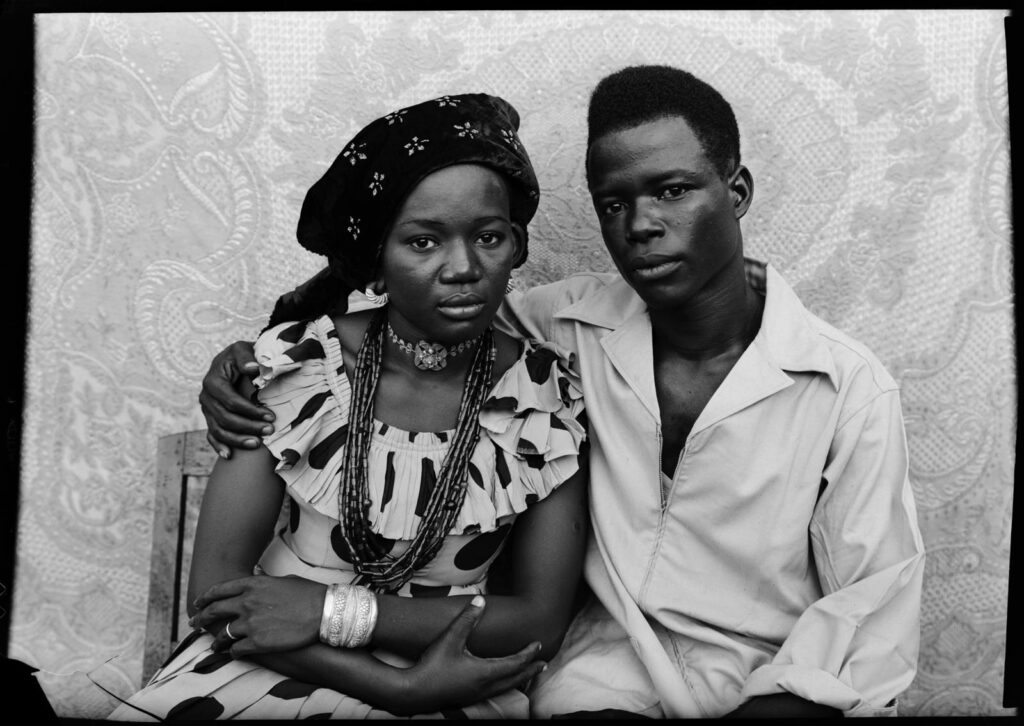

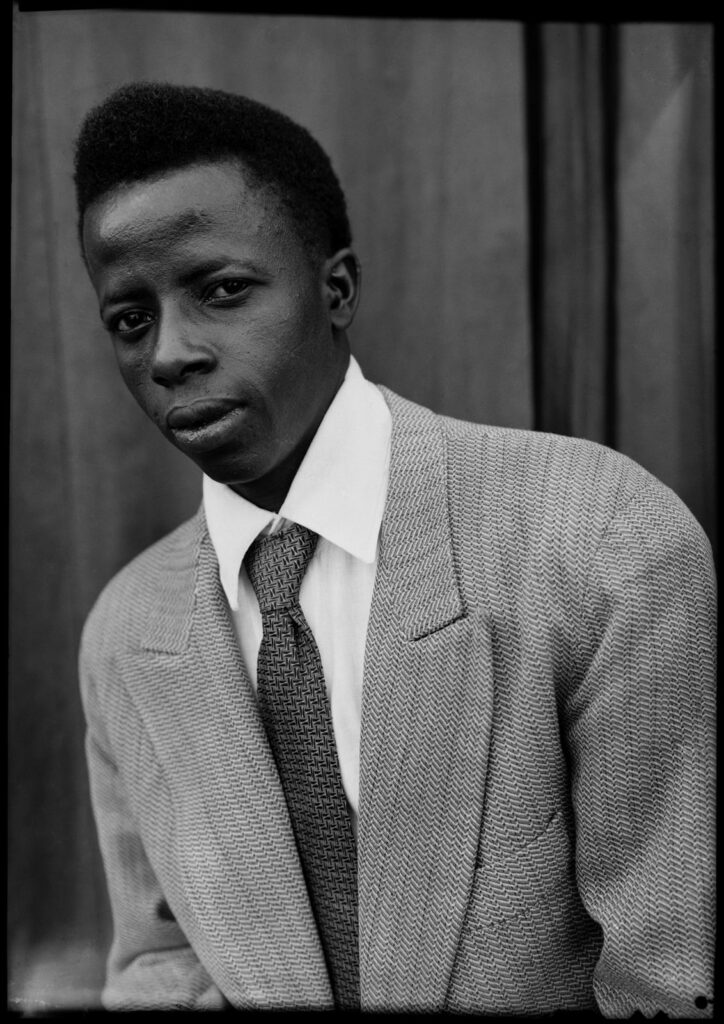

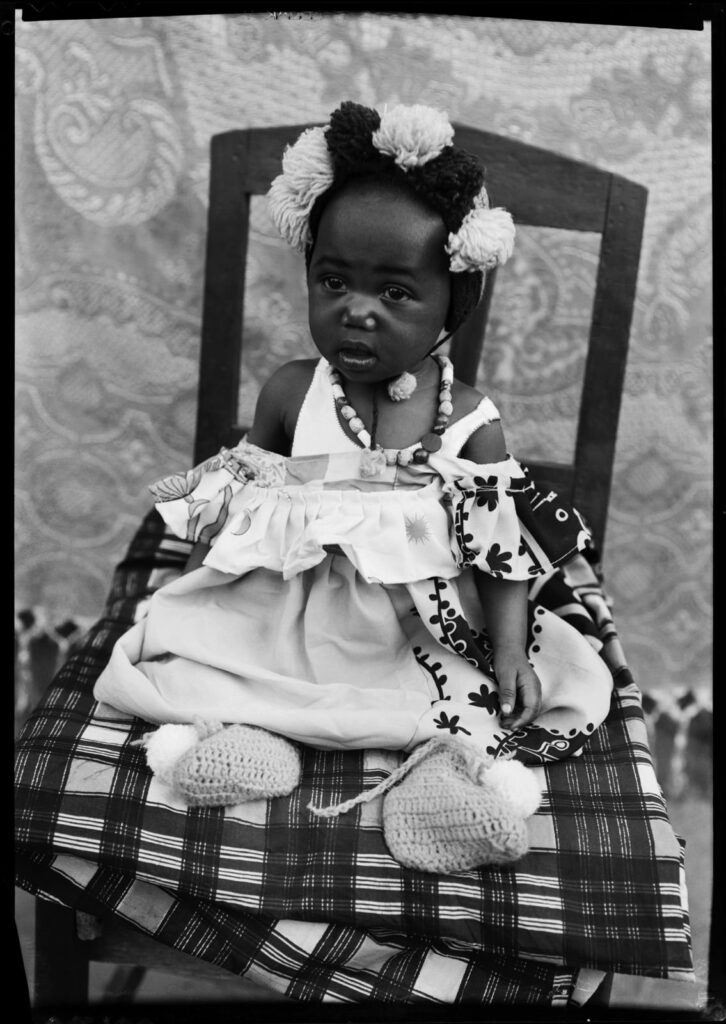

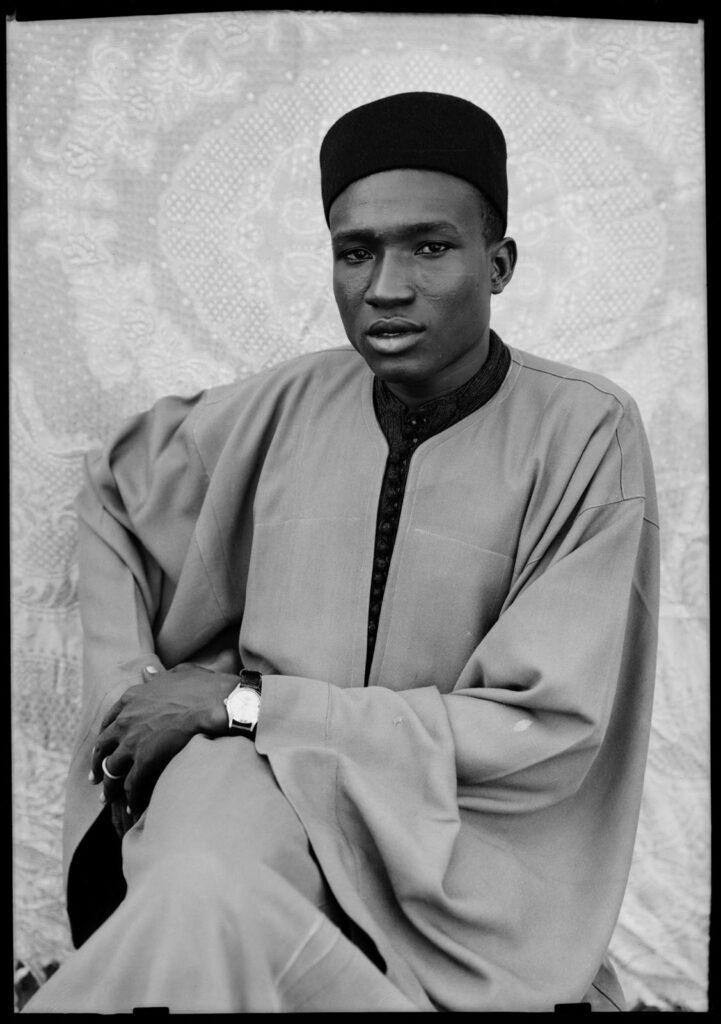

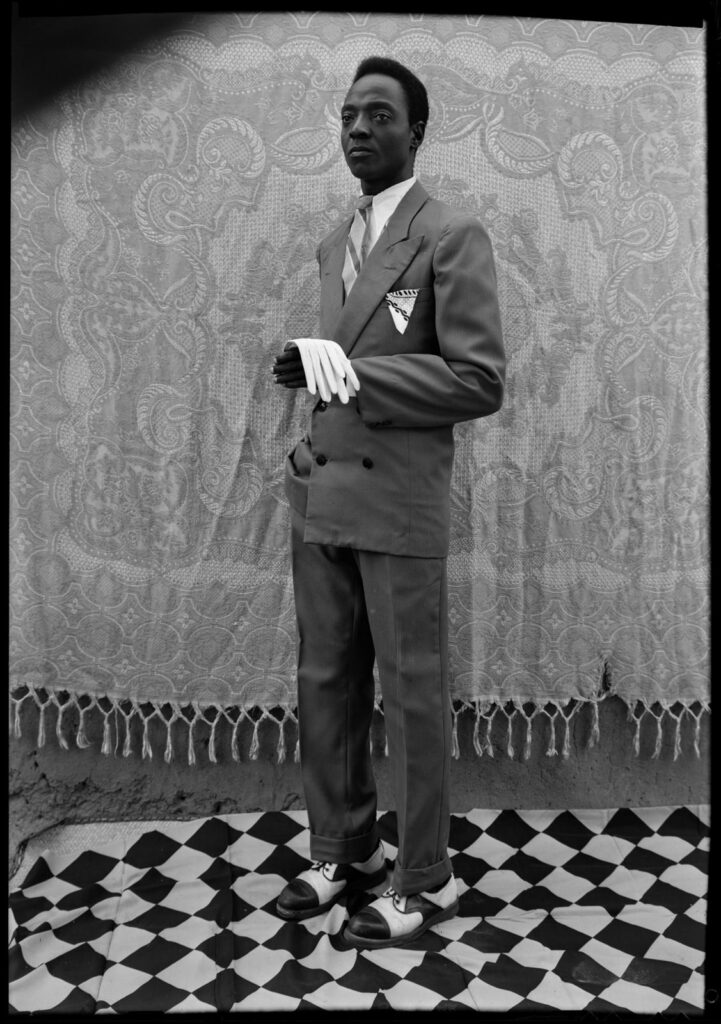

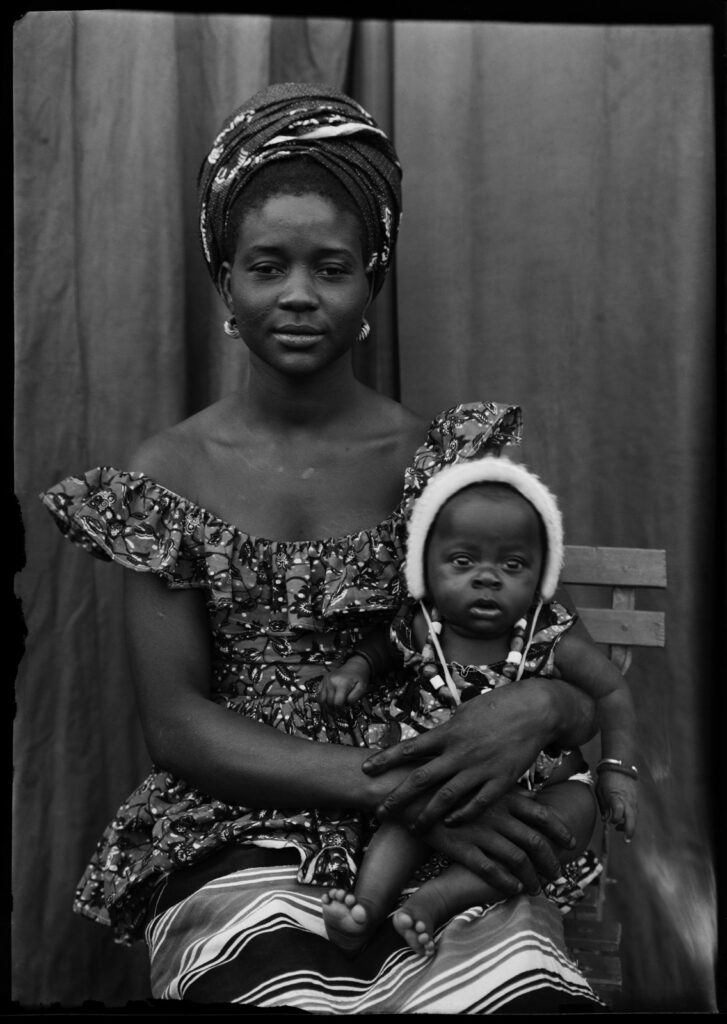

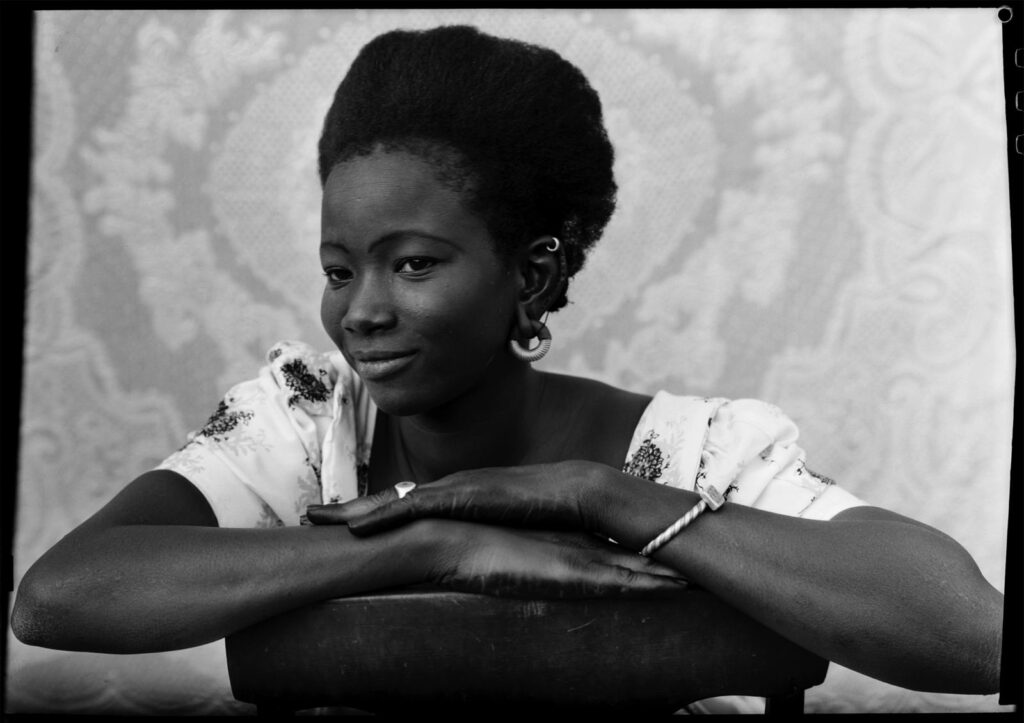

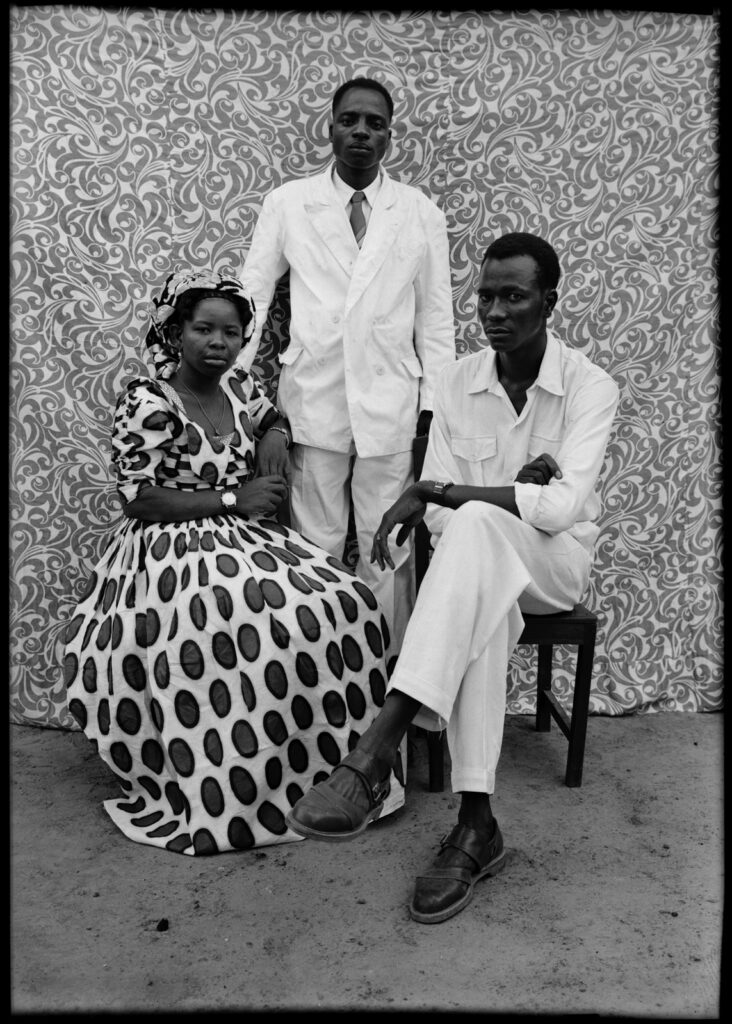

Keïta’s portraits were different. They were intimate yet regal, poised yet effortless. He combined the formal elegance of European studio photography with a distinctly Malian sensibility. His clients posed with dignity and style, their individuality amplified by his meticulous eye for composition. He carefully guided them, suggesting the perfect posture, adjusting the tilt of a head, the placement of a hand. “It’s easy to take a photo,” he once reflected, “but what really made a difference was that I always knew how to find the right position. I was never wrong.”

The Artist’s Eye: A Vision of Style and Identity

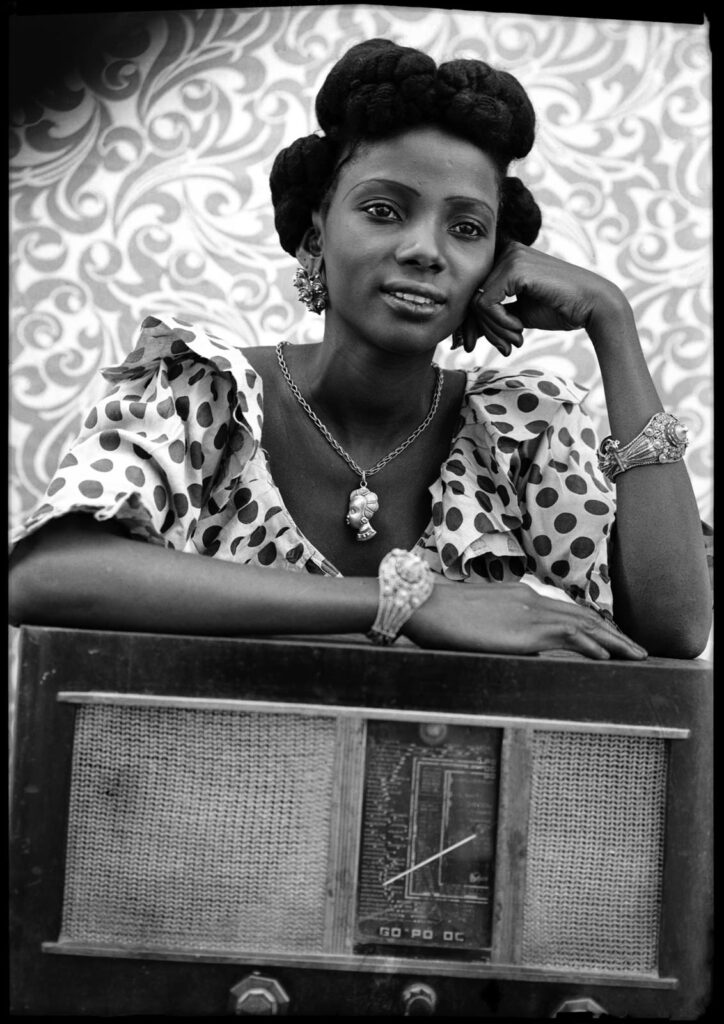

Keïta’s work was an artful balance of spontaneity and precision. He understood that a photograph was more than just an image—it was a statement. With his signature use of richly patterned backdrops, carefully curated props, and dramatic natural lighting, he transformed his subjects into icons of elegance and confidence.

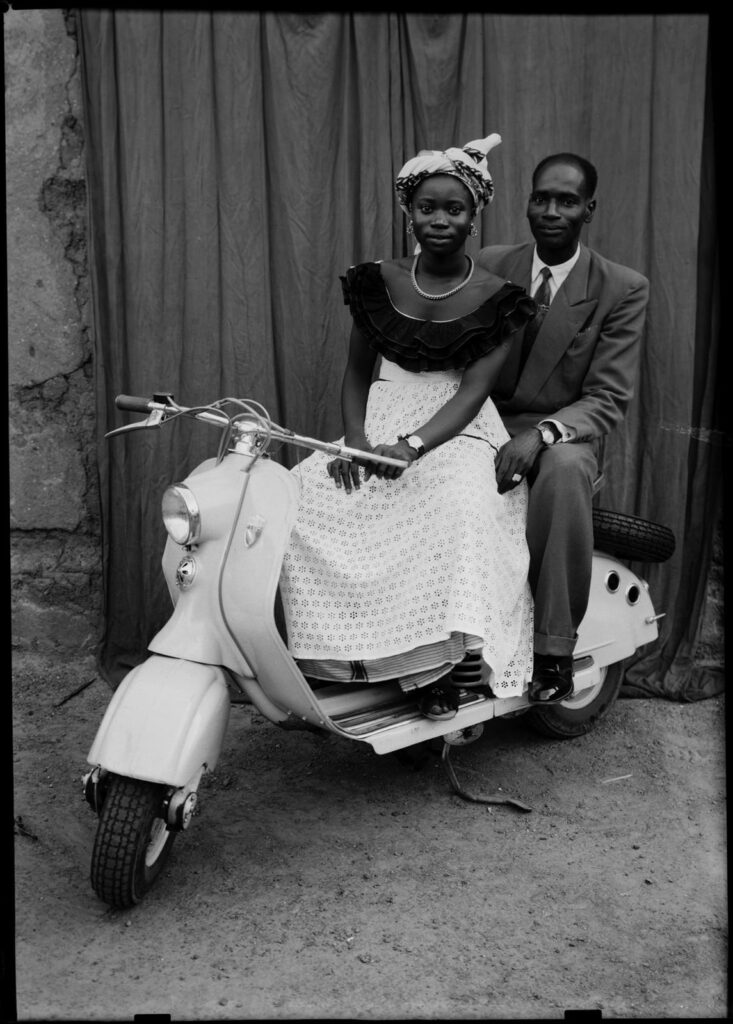

One of his most memorable portraits features a woman dressed in a flowing, intricately patterned gown, her hands delicately intertwined, her gaze direct yet enigmatic. The composition is effortless, yet every detail—the fabric, the posture, the interplay of textures—feels intentional. In another striking image, a young man leans casually against a Vespa scooter, exuding quiet pride and modern ambition. The scene is simple, but the message is profound: this is a new generation, embracing progress while staying rooted in identity.

Keïta provided his clients with an assortment of European accessories—watches, pens, radios, and even Western-style suits—to project a sense of aspiration. Some brought their own prized possessions, eager to immortalize themselves with symbols of status and modernity. These choices, subtle yet powerful, spoke volumes about the changing tides of Malian society.

An Archivist of a Nation

By the 1950s, Keïta had become the most sought-after portraitist in Bamako. He meticulously preserved his negatives—thousands upon thousands of them—documenting a period of immense social transformation. Mali was shifting, redefining itself in the post-colonial era, and Keïta’s portraits captured this transition with remarkable sensitivity.

Yet, for all his success, he worked with striking simplicity. He used only natural light, favoring the soft, even illumination that filtered through his courtyard. And in an era when film was expensive and precious, he took just a single shot per subject. No second chances, no retakes—just an unerring instinct for perfection.

By 1962, as Mali celebrated its newfound independence, Keïta was called upon to serve as the official government photographer. It was a prestigious role, but it came at a cost: his beloved studio was shut down in 1963, and his focus shifted from personal portraiture to state documentation. In 1977, as color photography took over and reshaped the industry, he quietly retired. His work, once the pride of Bamako, faded into obscurity.

The Rediscovery: From Bamako to the World

For decades, Keïta’s archive remained hidden—a treasure trove of Malian history locked away in negatives. Then, in the early 1990s, his work resurfaced in an exhibition in New York. The photographs were shown anonymously, yet they mesmerized audiences. The portraits were too striking, too refined, too evocative to be ignored. Art curator André Magnin, captivated by their brilliance, embarked on a journey to track down the artist behind the images.

When Keïta was finally rediscovered, his reputation soared. His first solo exhibition in 1994 at the Fondation Cartier in Paris introduced him to the international art world. Museums, galleries, and collectors clamored to showcase his work, and suddenly, the world recognized what Mali had known all along—Seydou Keïta was not just a photographer. He was an artist of the highest caliber, a visionary who had preserved the soul of a nation in silver gelatin.

The Legacy of Seydou Keïta

Keïta’s work is more than a historical record—it is a celebration of identity, dignity, and self-expression. His portraits are not just images of individuals; they are echoes of an era, stories frozen in time, each one a testament to the pride and poise of a people in transition.

Despite the years of obscurity, his legacy endures. Today, his photographs are displayed in the most prestigious museums and galleries around the world. Posthumous editions of his work are carefully curated and exhibited, ensuring that his vision remains alive. His images continue to inspire, reminding us that portraiture is not merely about faces—it is about the lives, emotions, and stories behind them.

Seydou Keïta passed away in 2001, but his work remains timeless. Through his lens, Mali lives on, elegant and unyielding. His photographs are more than just art; they are a declaration—of beauty, of culture, of humanity. And in them, Seydou Keïta’s spirit remains forever in focus.